Abstract

Among GIT related health problems, diarrhoea is a major concern and often becomes cause of mortality in children worldwide. Plant based treatments rather than conventional medicines could be safer modes of managing this illness with no or minimal adverse effects. In these regards, phytochemicals and antidiarrheal activity of two extracts, aqueous and methanolic, of a traditionally used plant Camonea bifida leaves were studied in mice by castor oil-induced diarrhoeal model to get an insight about their effectiveness. Study reveals that both extracts contain almost similar phytoconstituents namely flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, reduce sugar and phytosterols. But the antidiarrheal study provides a competitive result demonstrating that methanolic extract possesses higher activity in a dose-dependent manner. Significant reduction of diarrhea (52.35%, p = 0.001 and 72.76%, p < 0.0001) by both doses (200mg and 400mg) of methanolic extracts reveals its higher potency compared to the two similar doses of aqueous extracts (20.41% and 32.65%). This variation in activity could be due to presence of different molecules or due to variability in the concentration of the existing phytochemicals. Further research may disclose the culinary mechanistic approaches of the extracts and the reasons behind the variability in effectiveness.

Cite

- MLA: Sohan, S. M.; Sarker, S. I.; Laji, M. A.; Ahsan, L.; Islam, M. R.; Metul, M. A.; Akter, T.. "In vivo Comparative Study of Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Activity between Aqueous and Methanolic Ex-tracts of Camonea bifida Leaves." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3.1 (2025): 83-88.

- APA: Sohan, S. M.; Sarker, S. I.; Laji, M. A.; Ahsan, L.; Islam, M. R.; Metul, M. A.; Akter, T., (2025). In vivo Comparative Study of Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Activity between Aqueous and Methanolic Ex-tracts of Camonea bifida Leaves. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), 83-88.

- Chicago: Sohan, S. M.; Sarker, S. I.; Laji, M. A.; Ahsan, L.; Islam, M. R.; Metul, M. A.; Akter, T.. "In vivo Comparative Study of Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Activity between Aqueous and Methanolic Ex-tracts of Camonea bifida Leaves." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3, no. 1 (2025): 83-88.

- Harvard: Sohan, S. M.; Sarker, S. I.; Laji, M. A.; Ahsan, L.; Islam, M. R.; Metul, M. A.; Akter, T., 2025. In vivo Comparative Study of Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Activity between Aqueous and Methanolic Ex-tracts of Camonea bifida Leaves. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), pp.83-88.

- Vancouver: Sohan, S. M.; Sarker, S. I.; Laji, M. A.; Ahsan, L.; Islam, M. R.; Metul, M. A.; Akter, T.. In vivo Comparative Study of Phytochemicals and Pharmacological Activity between Aqueous and Methanolic Ex-tracts of Camonea bifida Leaves. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm. 2025;3(1):83-88.

Keywords

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Group 1: Normal control (NC) group for both aqueous and methanolic extract received distilled water.

- Group 2: Positive control (PC) group for both aqueous and methanolic extract received standard drug, Loperamide, at a dosage of 3 mg/kg body weight (BW).

- Group 3: Test group (TG) treated with aqueous extract at a low dose of 200 mg/kg body weight (BW).

- Group 4: Test group (TG) treated with aqueous extract at a high dose of 400 mg/kg body weight (BW).

- Group 5: Test group (TG) treated with methanolic extract at a low dose of 200 mg/kg body weight (BW).

- Group 6: Test group (TG) treated with methanolic extract at a high dose of 400 mg/kg body weight (BW).

Thirty minutes after administration, all mice were given 0.5 mL of castor oil orally to induce diarrhoea and were individually placed in cages lined with non-absorbent blotting paper. The paper was changed every hour throughout the 4-hour observation period. During this time, the number of instances of diarrhoea was recorded, and the percentage of inhibition of defecation was calculated for each group of animals. The percentage inhibition of defecation from the NC group was determined using the following formula:

2.7 Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Qualitative Phytochemical Screening

Multiple tests of phytochemical screening indicate the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, reducing sugar, and phytosterols in the methanolic extract, where flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenols are the most abundant. On the other hand, preliminary phytochemical screening of aqueous extract revealed the presence of alkaloids, carbohydrates, ketones, reducing sugars, glycosides, cardiac glycosides, amino acids, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds (Table 1). The therapeutic potential of C. bifida might be due to the presence of these phytochemicals. For instance, flavonoids are known to have antioxidant effects, inhibiting the initiation, promotion, and progression of tumors. Alkaloids exhibit multiple therapeutic effects, including analgesic (pain-relieving), anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antihypertensive, and antimicrobial properties [11, 12].

Table 1. Phytochemical screening results obtained after testing the aqueous and methanolic extracts of C. bifida leaves

(-) sign indicates that the mentioned phytochemicals are absent, (+) sign indicates that the mentioned phytochemicals are present

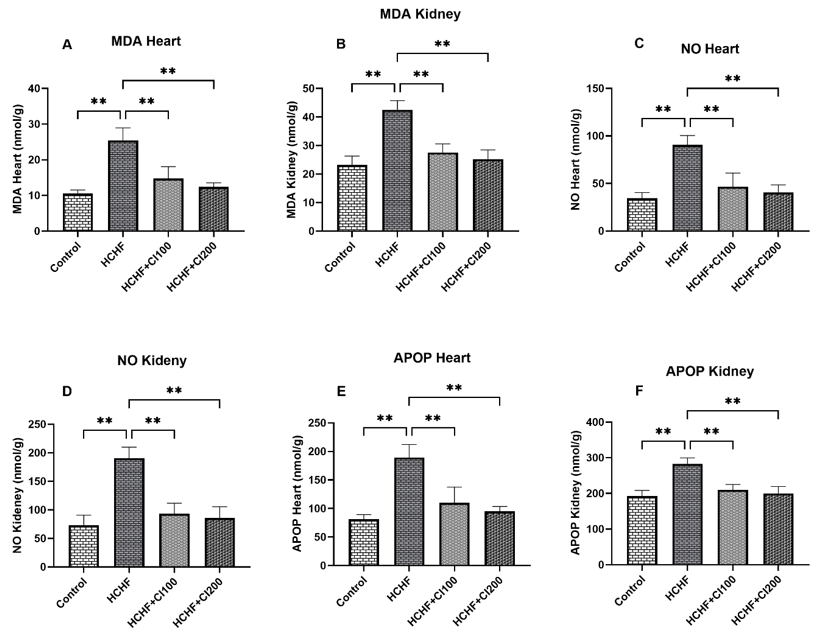

Both aqueous and methanolic extracts were assessed for their anti-diarrheal activity using the castor oil-induced method with mice as the animal model. The effect of extracts in mice is shown in Table 2. Loperamide (3 mg/kg) was taken as the standard drug. Both extracts of C. bifida demonstrated substantial anti-diarrheal activity, where the value was more significant for the methanolic extracts of 200 mg/kg (4.67 ± 0.67) and 400 mg/kg (2.67 ± 0.67) BW. But no significant effect was observed by the lower dose of aqueous extract. All extracts showed a reducing effect on diarrhea; however, the extracts for the last three groups were significant, indicating a notable dose-dependent anti-diarrheal activity. The doses of 200 and 400 mg/kg of the two plant extracts caused dose-dependent inhibition of diarrheal response induced by castor oil. The extracts exhibited 20.41%, 32.65%, 52.35% and 72.76% inhibition of diarrhea in mice, respectively, after 4 hours of oral administration. On the other hand, the standard drug, Loperamide, exhibited 61.22% inhibition at a 3 mg/kg BW dose.

4. Discussion

In this study, diarrhea was intentionally induced using castor oil as a model for experimental purposes. This model is considered the gold standard for assessing the antidiarrheal effects of substances because it closely mimics the natural pathophysiological processes involved in diarrhea [15]. Compared to the NC group, both extracts of C. bifida leaves exhibited antidiarrheal activity. However, both test doses of the methanolic extract showed a significant and remarkable effect (P < 0.001, P < 0.0001) in the castor oil-induced diarrhea model. On the other hand, a low dose (200mg/kg) of aqueous extract showed no or minimal effect. The total and average number of stools were calculated and examined as an indicator of comparison. The extracts demonstrated a dose-dependent response in this model, indicating that the highest dose (400 mg/kg) resulted in the maximum antidiarrheal activity, with a defecation inhibition percentage of 72.76%. The presence of plant metabolites, such as flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, reducing sugars, saponins, sterols, or terpenes, has been proven to cause relief of diarrheal symptoms [16]. Asmi et al. also reported that flavonoids have the ability to reduce diarrheal conditions by suppressing intestinal secretion, reducing intestinal motility, and hydroelectric discharges [17]. The presence of flavonoids in both extracts could be a possible reason for their antidiarrheal activity.

5. Conclusion

Both extracts, aqueous and methanolic, of C. bifida leaves contain a considerable amount of phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, reducing sugar, and phytosterols, but the methanolic extract showed excellent antidiarrheal effect. The results obtained from this research could provide valuable insights for natural product researchers. This study is needed to expand our understanding of the underlying cause of the therapeutic effect. Further, NMR or GC-MS study of the phytochemicals can be done to isolate and identify the active compounds, which could be a lead compound in developing a new therapeutic molecule.

Author Contributions

TST came up with the idea for the investigation and planned, TB, SA carried out all laboratory tests, TIT, AT analyzed and interpreted test results. The study's conception and design, as well as its writing and editing, involved TB, SA, TIT, AT and TST. The manuscript's submitted version was approved by all authors.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Florez, I.D.; Nino-Serna, L.F.; Beltran-Arroyave, C.P. Acute infectious diarrhea and gastroenteritis in children. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2020, 22, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-020-0713-6

- Schiller, L.R. Diarrhea. Med. Clin. North Am. 2000, 84, 1259–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70286-8

- Burgers, K.; Lindberg, B.; Bevis, Z.J. Chronic diarrhea in adults: evaluation and differential diagnosis. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 472–480.

- Zheng, Z.; Srinual, S.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Du, T.; Hu, M.; Sun, R.; Gao, S. Herbal Medicines as Adjuvants for the Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea. Drug Metab. 2023. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200224666230817102224

- Chandra, K.A.; Wanda, D. Traditional method of initial diarrhea treatment in children. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2017, 40, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694193.2017.1386980

- Yadav, S.; Hemke, A.; Umekar, M. Convolvulaceae: A Morning glory plant review. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2018, 51, 103–117.

- Akter, S.; Jahan, I.; Khatun, M.R.; Khan, M.F.; Arshad, L.; Jakaria, M.; Haque, M.A. Pharmacological insights into Merremia vitifolia (Burm. f.) Hallier f. leaf for its antioxidant, thrombolytic, anti-arthritic and anti-nociceptive potential. Rep. 2021, 41, BSR20203022. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20203022

- Olatunji, T.L.; Adetunji, A.E.; Olisah, C.; Idris, O.A.; Saliu, O.D.; Siebert, F. Research Progression of the Genus Merremia: A Comprehensive Review on the Nutritional Value, Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicity. Plants 2021, 10, 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10102070

- Shaikh, J.R.; Patil, M. Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 603–608. https://doi.org/10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2i.8834

- Shoba, F.G.; Thomas, M. Study of antidiarrhoeal activity of four medicinal plants in castor-oil induced diarrhoea. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00379-2

- Singh, S.; Bansal, A.; Singh, V.; Chopra, T.; Poddar, J. Flavonoids, alkaloids and terpenoids: a new hope for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2022, 21, 941–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00943-8

- Rajput, A.; Sharma, R.; Bharti, R. Pharmacological activities and toxicities of alkaloids on human health. Today: Proc. 2022, 48, 1407–1415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.189

- Widyawati, P.S.; Budianta, T.D.; Kusuma, F.A.; Wijaya, E.L. Difference of solvent polarity to phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of Pluchea indicia less leaves extracts. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2014, 6, 850–855.

- Barchan, A.; Bakkali, M.; Arakrak, A.; Pagán, R.; Laglaoui, A. The effects of solvents polarity on the phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of three Mentha species extracts. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 399–412.

- Rahman, M.K. Antidiarrheal and thrombolytic effects of methanol extract of Wikstroemia indica (L.) CA Mey leaves. J. Green Pharm. 2015, 9, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-8258.150914

- Venkatesan, N.; Thiyagarajan, V.; Narayanan, S.; Arul, A.; Raja, S.; Kumar, S.V.; Rajarajan, T.; Perianayagam, J.B. Anti-diarrhoeal potential of Asparagus racemosus wild root extracts in laboratory animals. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 8, 39–46.

- Asmi, K.S.; Lakshmi, T.; Balusamy, S.R.; Parameswari, R. Therapeutic aspects of taxifolin—an update. Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 187–189.

- Degu, A.; Engidawork, E.; Shibeshi, W. Evaluation of the anti-diarrheal activity of the leaf extract of Croton macrostachyus ex Del. (Euphorbiaceae) in mice model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1357-9

- Maria, N.N.; Jasmin, A.A.; Tahmida, U.; Singha, S.; Ahsan, T. Investigation on Anti‐Diarrheal and Antipyretic Activities of Citrus maxima Seeds in Swiss Albino Mice Model. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e4631. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4631

- Afrin, S.R.; Islam, M.R.; Didari, S.S.; Jannat, S.W.; Nisat, U.T.; Hossain, M.K. Investigation of hypoglycemic and antidiarrheal activity on mice model and in vitro anthelmintic study of Macropanax dispermus (Blume) Kuntze (Araliaceae): a promising ethnomedicinal plant. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 482–490. https://doi.org/10.34172/jhp.2024.51515

- Awouters, F.; Niemegeers, C.J.E.; Lenaerts, F.M.; Janssen, P.A.J. Delay of castor oil diarrhoea in rats: a new way to evaluate inhibitors of prostaglandin biosynthesis. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1978, 30, 41–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1978.tb13150.x

- Liang, Y.-C.; Liu, H.-J.; Chen, S.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Chou, L.-S.; Tsai, L.H. Effect of lipopolysaccharide on diarrhea and gastrointestinal transit in mice: roles of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 357. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.357

- Scholtka, B.; Stümpel, F.; Jungermann, K. Acute increase, stimulated by prostaglandin E2, in glucose absorption via the sodium dependent glucose transporter-1 in rat intestine. Gut 1999, 44, 490–496. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.44.4.490

Author Affiliation

1Department of Pharmacy, School of Science, Primeasia University, Banani, Bangladesh

2Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science, Comilla University, Cumilla, Bangladesh

ARTICLE INFO

Dr. Elias Al Mamun, Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical technology, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh