Abstract

Cite

- MLA: Md. Sazid Sharier, Puspa Sornokar, Hridoy Chandra Ghosh, Fatiha Fauzia, Md Sajjad Hossain Mia, Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Khondoker Shahin Ahmed, Hemayet Hossain, Nusrat Subhan, Md. Ashraful Alam, Md. Nurul Islam. "Evaluation of Reno-Protective Effect of Asparagus racemosus Root Extract in Isoproterenol-Induced Rats." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3.1 (2025): 38-54.

- APA: Md. Sazid Sharier, Puspa Sornokar, Hridoy Chandra Ghosh, Fatiha Fauzia, Md Sajjad Hossain Mia, Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Khondoker Shahin Ahmed, Hemayet Hossain, Nusrat Subhan, Md. Ashraful Alam, Md. Nurul Islam, (2025). Evaluation of Reno-Protective Effect of Asparagus racemosus Root Extract in Isoproterenol-Induced Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), 38-54.

- Chicago: Md. Sazid Sharier, Puspa Sornokar, Hridoy Chandra Ghosh, Fatiha Fauzia, Md Sajjad Hossain Mia, Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Khondoker Shahin Ahmed, Hemayet Hossain, Nusrat Subhan, Md. Ashraful Alam, Md. Nurul Islam. "Evaluation of Reno-Protective Effect of Asparagus racemosus Root Extract in Isoproterenol-Induced Rats." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3, no. 1 (2025): 38-54.

- Harvard: Md. Sazid Sharier, Puspa Sornokar, Hridoy Chandra Ghosh, Fatiha Fauzia, Md Sajjad Hossain Mia, Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Khondoker Shahin Ahmed, Hemayet Hossain, Nusrat Subhan, Md. Ashraful Alam, Md. Nurul Islam, 2025. Evaluation of Reno-Protective Effect of Asparagus racemosus Root Extract in Isoproterenol-Induced Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), pp.38-54.

- Vancouver: Md. Sazid Sharier, Puspa Sornokar, Hridoy Chandra Ghosh, Fatiha Fauzia, Md Sajjad Hossain Mia, Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Khondoker Shahin Ahmed, Hemayet Hossain, Nusrat Subhan, Md. Ashraful Alam, Md. Nurul Islam. Evaluation of Reno-Protective Effect of Asparagus racemosus Root Extract in Isoproterenol-Induced Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm. 2025;3(1):38-54.

Keywords

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Isoprenaline hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Reagents and standards required for myeloperoxidase (MPO), malondialdehyde (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP) assays, Catalase (CAT), along with Picrosirius red staining materials, were sourced from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich. standards and associated assay components were procured from SR Group (Delhi, India). Commercial kits for uric acid, and creatinine analyses were purchased from DCI Diagnostics (Budapest, Hungary).

2.2 Preparation of A. racemosus Root Extracts

The roots of Asparagus racemosus were sourced from the local market of Basundhara, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Specimen identification occurred at the Mirpur National Herbarium, Bangladesh, and the voucher number was documented in the Herbarium (DACB Accession Number DACB-87262). After collection, the roots were oven-dried at 50°C and then finely ground into a powder. A total of 500 g of the powdered material was macerated in methanol within a sealed glass container and stored in a dark environment at ambient temperature for five days, with intermittent shaking. The resulting mixture was filtered to obtain the methanolic extract. Ethanol was subsequently removed using a rotary evaporator set at 50°C and 100rpm, yielding a concentrated crude extract. An identical procedure was employed to prepare the methanolic extract. Both extracts, characterized by a sticky, dark-brown appearance, were subjected to phytochemical profiling using a high-performance liquid chromatography with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD) method.

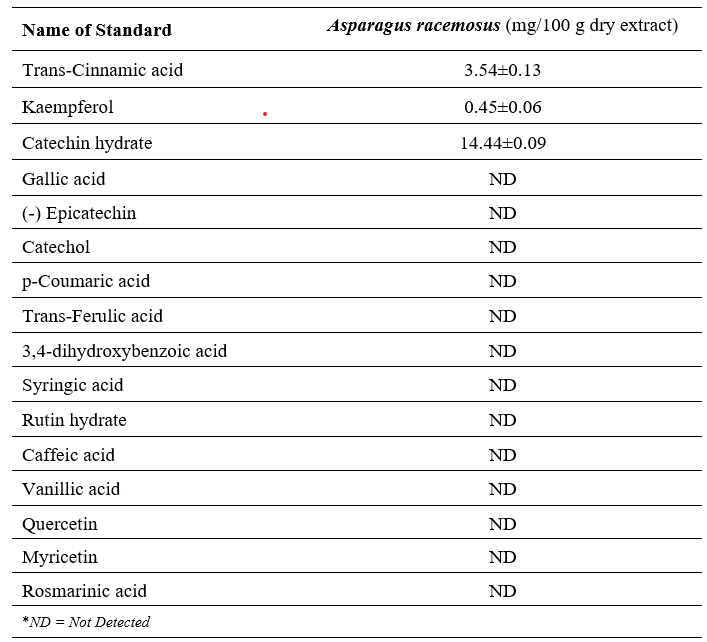

2.3 HPLC-DAD Analysis of A. racemosus Root Extracts

High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD) was performed using a Shimadzu LC-20A system (Japan), comprising a binary pump (LC-20AT), autosampler (SIL-20A HT), column oven (CTO-20A), and photodiode array detector (SPD-M20A), all operated via LC Solution software. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a Luna C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex), maintained at a constant temperature of 33 °C.

2.4 Chromatographic Conditions

Quantitative analysis of selected polyphenolic constituents in the ethanolic extract of Asparagus racemosus was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with diode-array detection (HPLC-DAD), following the protocol outlined by Ahmed et al.[31], with slight procedural adjustments. The chromatographic separation employed a binary mobile phase system comprising 1% acetic acid in acetonitrile (Solvent A) and 1% acetic acid in water (Solvent B). The gradient elution profile was programmed as follows: 5–25% A (0.01–20 min), 25–40% A (20–30 min), 40–60% A (30–35 min), 60–30% A (35–40 min), 30–5% A (40–45 min), and maintained at 5% A (45–50 min). A sample volume of 20 μL was injected per run, with a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. Detection was carried out at 270 nm to ensure method validation and compound identification. Prior to use, the mobile phase was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane (India) and degassed under vacuum conditions.

2.5 Preparation of Working Standard Solutions for HPLC Analysis

Sixteen phenolic compounds were individually dissolved in methanol using 25 mL volumetric flasks to prepare standard stock solutions, with concentrations ranging from 4.0 to 50 µg/mL. Appropriate aliquots from each stock were combined and serially diluted with methanol to generate the working standard solutions. All prepared solutions were stored under refrigerated conditions to maintain stability.

For calibration curve development, a composite standard solution was formulated in methanol containing the following concentrations: gallic acid (20 µg/mL), 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (15 µg/mL), catechin hydrate (50 µg/mL), catechol, (-)-epicatechin, and rosmarinic acid (30 µg/mL each), caffeic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, rutin hydrate, p-coumaric acid, trans-ferulic acid, and quercetin (10 µg/mL each), myricetin and kaempferol (8 µg/mL each), and trans-cinnamic acid (4 µg/mL). Additionally, an ethanolic solution of Asparagus racemosus extract was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL and stored under refrigeration until analysis.

2.6 Experimental animals

Twenty-four male Long Evans rats, aged 8–10 weeks and weighing between 180–190 g, were procured from the animal facility of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, for this study. The animals were housed under standardized laboratory conditions, including a 12-hour light/dark cycle, relative humidity of approximately 55%, and a controlled temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. All procedures adhered to international ethical guidelines outlined by the Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and the International Council for Laboratory Animal Science (ICLAS). Ethical approval for the experimental protocols was granted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of North South University (Approval No. 2024/OR-NSU/IACUC0107).

2.7 Experimental design and treatment protocol

The rats were divided into four groups, each group consisting of 6 rats. The groups were as such.

- Control group.

- ISO (Isoprenaline) group

- Control + A. racemosus group.

- ISO + A. racemosus group.

The control group was fed a diet consisting of chow food and drinking water. The ISO group was administered with 50 mg/kg of isoprenaline subcutaneously every 3 days for 2 weeks. Water and chow food were given to the ISO group along with the isoprenaline. The Control + Methanol extract of A. racemosus group was also given chow food and water, and additionally, the methanol extract of A. racemosus was also administered orally at a dose of 100 mg/kg daily for 2 weeks. The group ISO + ethanolic extract of A. racemosus was given both ISO and extract of A. racemosus. The ISO + Methanolic extract of A. racemosus group received isoprenaline subcutaneously at a dose of 50 mg/kg every 3 days for 2 weeks and ethanolic extract of A. racemosus was administered orally, using a stainless steel gavage needle, at a dose of 100 mg/kg daily for 2 weeks. The ISO + ethanolic extract of A. racemosus group was additionally fed chow food and water. After completion of 14 days of the procedure, the rats were weighed and then sacrificed on the 15th day. Blood was collected and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, with a temperature of 4 °C in order to collect the plasma. Following that, the required organs left and right kidneys were collected and weighed. The harvested organs, kidney tissues were stored for bioassay and one part of the kidney was stored in neutral buffer formalin for the use of histology staining. The plasma and tissues collected for bioassay were stored at −18 °C preserved for bioassay analysis. A portion of the kidney tissue was fixed in neutral buffered formalin for histological examination. All plasma and tissue samples designated for bioassay were stored at −18 °C until further use.

2.8 Induction of Myocardial Infarction

Rats were given subcutaneous injections of 50 mg/kg of isoprenaline (ISO) hydrochloride, dissolved in physiological solution, to induce an experimental myocardial infarction.

2.9 Determination of Kidney Function via Creatinine and Uric Acid Measurement

Kidney specific marker tests such as creatinine, and uric acid were also performed using plasma following the manufacturer's protocol.

2.10 Preparing a Tissue Sample for Oxidative Stress Marker Evaluation

To separate the supernatant, the heart and kidney tissues were homogenized in 10% phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. After being collected, the supernatants were utilized in enzymatic and protein analyses.

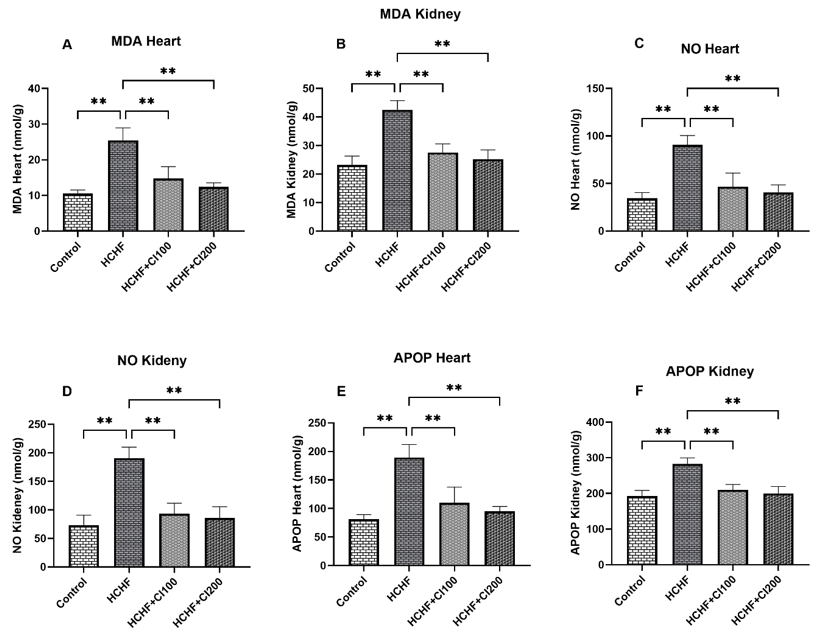

2.11 Malondialdehyde estimation (MDA)

The accumulation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), a byproduct of polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation, serves as a key indicator of oxidative stress. Quantification of TBARS in kidney tissue homogenates, was performed following a previously established protocol with minor adjustments [32, 33]. The assay involved heating the reaction mixture, followed by cooling and spectrophotometric measurement of the supernatant’s absorbance at 535 nm against a reagent blank. Each reaction mixture comprised 0.1 mL of sample and 2 mL of TBA-TCA-HCl reagent, containing thiobarbituric acid, trichloroacetic acid, and hydrochloric acid. TBARS concentrations were calculated using a standard curve generated from 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane and expressed as nmol/g for tissue samples.

2.12 Nitric oxide estimation (NO)

Nitric oxide concentrations in tissue homogenates were quantified using a modified Griess-Illosvoy method, following previously established protocols [34-36]. Briefly, the reaction mixture—comprising phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), tissue homogenate, and the reagent—was incubated at 25 °C for 150 minutes, resulting in the formation of a pink chromophore. Absorbance was recorded at 540 nm against a reagent blank. NO levels were calculated using a standard curve and expressed as nanomoles per gram of tissue (nmol/g).

2.13 Estimation of Advanced Protein Oxidation Products (AOPP)

Advanced protein oxidation products (AOPP), a key biomarker of oxidative stress, were quantified following previously established methodologies [35, 37, 38]. The assay involved measuring the absorbance of chloramine-T in a reaction mixture composed of plasma diluted in phosphate-buffered solution, potassium iodide, and acetic acid. Absorbance was recorded immediately at 340 nm against a reagent blank. The response was linear across a concentration range of 0–100 nmol/mL, enabling accurate quantification of AOPP levels.

2.14 Estimation of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a key marker of tissue inflammation, was quantified using a modified o-dianisidine–hydrogen peroxide assay, as previously described [35, 39, 40].In brief, tissue homogenates containing 10 µg of protein were added in triplicate to a reaction mixture comprising o-dianisidine dihydrochloride (0.53 mM) and hydrogen peroxide (0.15 mM) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The enzymatic activity was monitored by measuring the change in absorbance at 460 nm. MPO activity was calculated and expressed as units per milligram of protein (MPO/mg protein).

2.15 Determination of Catalase (CAT) Activity

Catalase activity in serum and tissue homogenates was assessed following the method previously described by Alam et al. [41], with minor modifications. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mmol phosphate buffer (pH 5.0), 5.9 mmol hydrogen peroxide, and 0.1 mL of enzyme extract. The decomposition of hydrogen peroxide was monitored by measuring the change in absorbance at 240 nm. A change of 0.01 absorbance units per minute was defined as one unit of catalase activity and expressed accordingly.

2.16 Histopathological Evaluation

For microscopic examination, excised kidney and heart tissues from experimental rats were initially fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF). The fixed specimens were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin to prevent air entrapment. Thin sections approximately 5 µm in thickness were prepared using a rotary microtome and mounted onto clean glass slides. These sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to assess inflammatory cell infiltration. Additionally, Picrosirius Red staining was performed to visualize and evaluate fibrotic alterations. All stained slides were imaged and analyzed under a light microscope (Zeiss Axioscope) at 40× magnification.

2.17 Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical evaluations were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9. Group comparisons were conducted via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to identify significant differences among treatment groups. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

3. Results

4. Discussion

The present study highlights the reno-protective and antioxidant effects of ethanolic extract of Asparagus racemosus, offering strong evidence for its therapeutic potential in reducing isoproterenol (ISO) induced renal injury. HPLC-DAD analysis confirmed the presence of three major polyphenolics catechin hydrate, trans-cinnamic acid, and kaempferol. These compounds are widely recognized for their potent antioxidant [43], anti-inflammatory [43, 44], and cytoprotective actions [45], which may underlie the beneficial outcomes observed reducing of renal dysfunction in the experimental groups [46, 47].

Biochemical analysis demonstrated that isoproterenol (ISO) induced renal dysfunction, as reflected by significant elevations in serum creatinine, uric acid, and oxidative stress markers such as increased levels of lipid peroxidation (MDA), nitric oxide (NO) and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP). These changes are consistent with impaired renal clearance and free radical-mediated injury [45, 48]. Notably, treatment with A. racemosus extract markedly reduced uric acid and creatinine levels, suggesting an improvement in glomerular filtration and renal functional status. The restored catalase activity suggests that the extract strengthens the body's natural antioxidant defenses, possibly by boosting enzyme function or neutralizing free radicals directly [49, 50]. The significant reduction in myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity further supports its anti-inflammatory potential, indicating reduced neutrophil infiltration and tissue damage [51, 52]. The reduction points to be dampened inflammatory response, which may be critical in preventing progression to chronic kidney damage [53, 54].

Markers of oxidative stress also demonstrated protective effects of the extract. ISO significantly increased lipid peroxidation (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP), while reducing antioxidant catalase activity [55-57]. Co-administration of A. racemosus significantly normalized these parameters, lowering oxidative damage and restoring catalase activity toward control values. This finding suggests that the extract enhances endogenous antioxidant defense while limiting radical-induced injury.

Histopathological observations corroborated the biochemical findings, providing visual confirmation of tissue-level damage and recovery. ISO exposure led to severe inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrosis [58], evident from H&E and Sirius red staining, respectively [16, 48, 59]. This fibrotic response is primarily driven by ISO-induced oxidative stress [60] and inflammatory signaling [61], which activate fibroblasts and promote excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition [62] —particularly collagen types I and III. Over time, this disrupts normal kidney architecture and impairs function [62]. These pathological changes were clearly visualized using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Sirius red staining. H&E staining revealed dense infiltration of inflammatory cells, tubular degeneration, and glomerular distortion [63], indicating acute tissue injury [64]. Sirius red staining, which specifically binds to collagen fibers, highlighted extensive collagen accumulation in the interstitial spaces [65], confirming the presence of fibrosis. Conversely, A. racemosus treatment preserved kidney architecture, reduced inflammatory infiltration, and mitigated collagen deposition. These findings indicate that the extract not only alleviates acute inflammation but may also limit fibrotic progression. Collectively, the results suggest that the bioactive compounds in A. racemosus contribute synergistically to renal protection by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, and tissue remodeling.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the bioactive compounds in A. racemosus act synergistically to provide renal protection by reducing oxidative stress, suppressing inflammation, and preventing fibrotic remodeling. This multifaceted mechanism positions A. racemosus as a promising candidate for the development of phytotherapeutic interventions in renal pathologies, particularly those driven by oxidative and inflammatory insults.

5. Limitations And Future Perspectives

Although the study provides strong preclinical evidence, it has some limitations. Only three polyphenolics were quantified, while other potentially active phytochemicals remain unexplored. The study was restricted to an isoproterenol-induced rat model, which may not fully mimic human renal pathology. Future research should focus on isolating and characterizing additional bioactive compounds, exploring molecular signaling pathways, and validating these findings in clinical trials. Long-term safety profiling is also essential before therapeutic translation.

6. Conclusion

The ethanolic extract of Asparagus racemosus, rich in polyphenolic compounds, exhibited strong reno-protective effects against isoproterenol-induced renal injury. By attenuating oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis, the extract preserved kidney function and histological integrity. These findings support its therapeutic potential as a natural adjunct in managing renal oxidative stress and related pathologies.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization, MAA and NS; methodology, MSS, PS, FF, SS, and HCG; software, KSA, HH, MNI, and MAA; validation, MAA, NS, and MNI; formal analysis, MA, and NS; investigation, FF, PS, MSHM, MTC and HCG; resources, MA, HCG, FF, and MSHM; data curation, FF, MA, MSHM and KSA; writing—original draft preparation, MSS, FF, MSHM, and HCG; writing—review and editing, FF, PS, and MAHM; visualization, MAA, NS and MNI; supervision, MAA, NS and MNI project administration, MAA and MNI; funding acquisition, MA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any internal or external funding from profit and non-profit organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The Authors gratefully acknowledge the logistic support from the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abebe, A.; Kumela, K.; Belay, M.; Kebede, B.; Wobie, Y. Mortality and predictors of acute kidney injury in adults: a hospital-based prospective observational study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94946-3

- Hoste, E. A. J.; Kellum, J. A.; Selby, N. M.; Zarbock, A.; Palevsky, P. M.; Bagshaw, S. M.; Goldstein, S. L.; Cerdá, J.; Chawla, L. S. Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14 (10), 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-018-0052-0

- Gevaert, S. A.; Hoste, E.; Kellum, J. A. Acute kidney injury. In Oxford Medicine Online; Oxford University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199687039.003.0068_update_001

- Meena, J.; Mathew, G.; Kumar, J.; Chanchlani, R. Incidence of Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Children: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2023, 151 (2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-058823

- Zoccali, C.; Bolignano, D. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. H1 Connect 2020. https://doi.org/10.3410/f.737386301.793572065

- Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, H.; Fan, K.; Jin, J.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Xie, R.; Li, C. Global, regional, and national burden inequality of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Med. 2025, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1501175

- Deng, L.; Guo, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yu, X.; Shuai, P. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease and its underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-21851-z

- Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Wu, H.; Fan, K.; Jin, J.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Xie, R.; Li, C. Global, regional, and national burden inequality of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Med. 2025, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1501175

- Petrosyan, H.; Torozyan, S. H.; Avoyan, H.; Hayrapetyan, H. Association between renal function and adverse outcomes in patients with st-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2025, 14 (Supplement_1). https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuaf044.112

- Khan, V.; Sharma, S.; Bhandari, U.; Ali, S. M.; Haque, S. E. Raspberry ketone protects against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Life Sci. 2018, 194, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2017.12.013

- Deferrari, G.; Cipriani, A.; La Porta, E. Renal dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases and its consequences. J. Nephrol. 2020, 34 (1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00842-w.

- Maarouf, R. E.; Azab, K. S.; Abdel-Rafei, M. K.; Mansour, S. Z.; Abubakr, A.; Abdelgayed, S. S.; Thabet, N. M.; El Bakary, N. M. Nattokinase Mitigates Myocardial Damage and Renal Dysfunction in γ-Irradiated Rats Treated with Isoproterenol. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x251332132

- Bekheit, S. O.; Kolieb, E.; El-Awady, E.-S. E.; Alwaili, M. A.; Alharthi, A.; Khodeer, D. M. Cardioprotective Effects of Ferulic Acid Through Inhibition of Advanced Glycation End Products in Diabetic Rats with Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Infarction. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18 (3), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030319

- Emran, T.; Chowdhury, N. I.; Sarker, M.; Bepari, A. K.; Hossain, M.; Rahman, G. M. S.; Reza, H. M. L-carnitine protects cardiac damage by reducing oxidative stress and inflammatory response via inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta against isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112139

- Wong, Z. W.; Thanikachalam, P. V.; Ramamurthy, S. Molecular understanding of the protective role of natural products on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 1145–1166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.009

- Zhou, W.; Fu, Y.; Xu, J.-S. Sophocarpine Alleviates Isoproterenol-Induced Kidney Injury by Suppressing Inflammation, Apoptosis, Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis. Molecules 2022, 27 (22), 7868. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227868

- Hasan, R.; Lasker, S.; Hasan, A.; Zerin, F.; Zamila, M.; Parvez, F.; Rahman, Md. M.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, Md. A. Canagliflozin ameliorates renal oxidative stress and inflammation by stimulating AMPK–Akt–eNOS pathway in the isoprenaline-induced oxidative stress model. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71599-2

- Gupta, K.; Bagang, N.; Singh, G.; Laddi, L. Rat Model of Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Injury. In Experimental Models of Cardiovascular Diseases; 2024; pp 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3846-0_9

- Alam, M. N.; Hossain, Md. M.; Rahman, Md. M.; Subhan, N.; Mamun, Md. A. A.; Ulla, A.; Reza, H. M.; Alam, Md. A. Astaxanthin Prevented Oxidative Stress in Heart and Kidneys of Isoproterenol-Administered Aged Rats. J. Diet. Suppl. 2017, 15 (1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390211.2017.1321078

- Alimullah, M.; Shuvo, A. U. H.; Jahan, I.; Ismail, I. N.; Islam, S. M. M.; Sultana, M.; Saad, M. R.; Raihan, S.; Khan, F.; Alam, Md. A.; Subhan, N. Evaluation of the modulating effect of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab in carbon-tetrachloride induce hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 38, 101689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2024.101689

- Sagor, Md. A. T.; Tabassum, N.; Potol, Md. A.; Alam, Md. A. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor, Allopurinol, Prevented Oxidative Stress, Fibrosis, and Myocardial Damage in Isoproterenol Induced Aged Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2015, 2015, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/478039

- Khan, M. A. H.; Ameer, O. Z.; Goorani, S.; Salman, I. M. Editorial: Debates in experimental pharmacology and drug discovery 2023: innovative approaches to chronic kidney disease drug discovery, identification of targets and safety assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1588367

- Khan, M. A.; Kassianos, A. J.; Hoy, W. E.; Alam, A. K.; Healy, H. G.; Gobe, G. C. Promoting Plant-Based Therapies for Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Evidence-Based Integrative Med. 2022, 27. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515690x221079688

- Shi, X.; Yin, H.; Shi, X. Bibliometric analysis of literature on natural medicines against chronic kidney disease from 2001 to 2024. Phytomedicine 2025, 138, 156410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156410

- Meher, D.; Singh, M.; Meher, B. An update on phytoconstituents and pharmacological importance of Asparagus racemosus. J. Appl. Pharm. Res. 2024, 12 (4), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.69857/joapr.v12i4.588

- Majumdar, S.; Gupta, S.; Prajapati, S. K.; Krishnamurthy, S. Neuro-nutraceutical potential of Asparagus racemosus: A review. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 145, 105013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105013

- Singh, N.; Garg, M.; Prajapati, P.; Singh, P. K.; Chopra, R.; Kumari, A.; Mittal, A. Adaptogenic property of Asparagus racemosus: Future trends and prospects. Heliyon 2023, 9 (4), e14932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14932

- Alok, S.; Jain, S. K.; Verma, A.; Kumar, M.; Mahor, A.; Sabharwal, M. Plant profile, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari): A review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013, 3 (3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2222-1808(13)60049-3

- Siddiqui, A. J.; Elkahoui, S.; Alshammari, A. M.; Patel, M.; Ghoniem, A. E. M.; Abdalla, R. A. H.; Dwivedi-Agnihotri, H.; Badraoui, R.; Adnan, M. Mechanistic Insights into the Anticancer Potential of Asparagus racemosus Willd. Against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation Study. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18 (3), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18030433

- Singh, R.; Geetanjali. Asparagus racemosus: a review on its phytochemical and therapeutic potential. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 30 (17), 1896–1908. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2015.1092148

- Ahmed, K. S.; Jahan, I. A.; Jahan, F.; Hosain, H. Antioxidant activities and simultaneous HPLC-DAD profiling of polyphenolic compounds from Moringa oleifera Lam. Leaves grown in Bangladesh. Food Res. 2021, 5 (1), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.26656/fr.2017.5(1).410

- Rajendran, R.; Krishnakumar, E. Hypolipidemic Activity of Chloroform Extract of Mimosa pudica Leaves. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2010, 2 (4), 215–221.

- Rahman, Md. M.; Alimullah, M.; Yasmin, T.; Akhter, N.; Ahmed, I.; Khan, F.; Saha, M.; Halim, M. A.; Subhan, N.; Haque, Md. A.; Alam, Md. A. Cardioprotective action of apocynin in isoproterenol‐induced cardiac damage is mediated through Nrf‐2/HO‐1 signaling pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12 (11), 9108–9122. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4465

- Tracey, W. R.; Tse, J.; Carter, G. Lipopolysaccharide-induced changes in plasma nitrite and nitrate concentrations in rats and mice: pharmacological evaluation of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995, 272 (3), 1011–1015. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3565(25)24521-9

- Mamun, F.; Rahman, Md. M.; Zamila, M.; Subhan, N.; Hossain, H.; Raquibul Hasan, S. M.; Alam, M. A.; Haque, Md. A. Polyphenolic compounds of litchi leaf augment kidney and heart functions in 2K1C rats. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2019.103662

- Alimullah, M.; Jahan, I.; Rahman, Md. M.; Khan, F.; Shahin Ahmed, K.; Hossain, Md. H.; Arabnozari, H.; Alam, Md. A.; Sarker, S. D.; Nahar, L.; Subhan, N. Camellia sinensis powder rich in epicatechin and polyphenols attenuates isoprenaline induced cardiac injury by activating the Nrf2 HO1 antioxidant pathway in rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08720-w

- Alimullah, M.; Rahman, N.; Sornaker, P.; Akramuddaula, K.; Sarif, S.; Siddiqua, S.; Mitu, K. F.; Jahan, I.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, Md. A. Evaluation of Terminalia arjuna Bark Powder Supplementation on Isoprenaline-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Heart of Long Evans Rats, Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of This Old Medicinal Plant. J. Med. Nat. Prod. 2024, 100004. https://doi.org/10.53941/jmnp.2024.100004

- Jahan, I.; Shuvo, A. U. H.; Alimullah, M.; Rahman, A. S. M. N.; Siddiqua, S.; Rafia, S.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, K. S.; Hossain, H.; Akramuddaula, K.; Alam, M. A.; Subhan, N. Purple potato extract modulates fat metabolizing genes expression, prevents oxidative stress, hepatic steatosis, and attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity in male rats. PLoS One 2025, 20 (4), e0318162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0318162

- Ulla, A.; Alam, M. A.; Sikder, B.; Sumi, F. A.; Rahman, M. M.; Habib, Z. F.; Mohammed, M. K.; Subhan, N.; Hossain, H.; Reza, H. M. Supplementation of Syzygium cumini seed powder prevented obesity, glucose intolerance, hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in high carbohydrate high fat diet induced obese rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1799-8

- Alimullah, M.; Barua Muthsuddy, I.; Alam, I.; Barua Joya, A.; Akhter, T.; Akter, A.; Amin, M. S.; Anmol Khan, S.; Alam, M. A.; Subhan, N. Evaluation of Mimosa pudica Leaf Extract on Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in Liver of Carbon Tetrachloride (CCl4) Administered Rats. J. Biosci. Exp. Pharmacol. 2024, 2 (1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.62624/jbep00.0011

- Alam, Md. A.; Chowdhury, M. R. H.; Jain, P.; Sagor, Md. A. T.; Reza, H. M. DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin prevents inflammation and oxidative stress of heart and kidney in two kidney and one clip (2K1C) rats. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2015, 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-015-0095-3

- Choucry, M. A.; Khalil, M. N. A.; El Awdan, S. A. Protective action of Crateva nurvala Buch. Ham extracts against renal ischaemia reperfusion injury in rats via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 214, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.11.034

- Alrumaihi, F.; Almatroodi, S. A.; Alharbi, H. O. A.; Alwanian, W. M.; Alharbi, F. A.; Almatroudi, A.; Rahmani, A. H. Pharmacological Potential of Kaempferol, a Flavonoid in the Management of Pathogenesis via Modulation of Inflammation and Other Biological Activities. Molecules 2024, 29 (9), 2007. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29092007

- Silva dos Santos, J.; Gonçalves Cirino, J. P.; de Oliveira Carvalho, P.; Ortega, M. M. The Pharmacological Action of Kaempferol in Central Nervous System Diseases: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.565700

- Hussain, M. S.; Altamimi, A. S. A.; Afzal, M.; Almalki, W. H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S. I.; Gupta, G.; Shahwan, M.; Kukreti, N.; Wong, L. S.; Kumarasamy, V.; Subramaniyan, V. Kaempferol: Paving the path for advanced treatments in aging-related diseases. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 188, 112389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2024.112389

- Herrera-Rocha, K. M.; Rocha-Guzmán, N. E.; Gallegos-Infante, J. A.; González-Laredo, R. F.; Larrosa-Pérez, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, M. R. Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids in Acetonic Extract from Quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.): Nutraceuticals with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. Molecules 2022, 27 (8), 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27082462

- Speisky, H.; Arias-Santé, M. F.; Fuentes, J. Oxidation of Quercetin and Kaempferol Markedly Amplifies Their Antioxidant, Cytoprotective, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Antioxidants 2023, 12 (1), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12010155

- Xing, Z.; Yang, C.; Feng, Y.; He, J.; Peng, C.; Li, D. Understanding aconite’s anti-fibrotic effects in cardiac fibrosis. Phytomedicine 2024, 122, 155112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155112

- Mbah, C. A.; Ikeyi, A. P.; Umeayo, C. I.; Nwaume, E. J.; Okonkwo, S. C. Investigating the Antioxidant Activity of Methanol Extract of Zapoteca portoricensis Root Using the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Method. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2025, 10 (3), 3206–3210. https://doi.org/10.38124/ijisrt/25mar326

- Skowronek, P.; Wójcik, Ł.; Strachecka, A. Impressive Impact of Hemp Extract on Antioxidant System in Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Organism. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (4), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11040707

- Hawkins, C. L.; Davies, M. J. Role of myeloperoxidase and oxidant formation in the extracellular environment in inflammation-induced tissue damage. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 633–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.07.007.

- Aratani, Y. Myeloperoxidase: Its role for host defense, inflammation, and neutrophil function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 640, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2018.01.004

- Tavares, E. de A.; Guerra, G. C. B.; da Costa Melo, N. M.; Dantas-Medeiros, R.; da Silva, E. C. S.; Andrade, A. W. L.; de Souza Araújo, D. F.; da Silva, V. C.; Zanatta, A. C.; de Carvalho, T. G.; de Araújo, A. A.; de Araújo-Júnior, R. F.; Zucolotto, S. M. Toxicity and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Phenolic-Rich Extract from Nopalea cochenillifera (Cactaceae): A Preclinical Study on the Prevention of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Plants 2023, 12 (3), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030594

- Shahid, A.; Inam-Ur-Raheem, M.; Socol, C. T.; Maerescu, C. M.; Criste, F. L.; Murtaza, H. B.; Bhat, Z. F.; Hussain, S.; Aadil, R. M. Investigating the anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory effects of “Gola” guava fruit and leaf extract in alleviating papain-induced knee osteoarthritis. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 2024, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2024.1442219

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Biswas, S.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Sarkar, C.; Datta, A. G. Effect of isoproterenol on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes of myocardial tissue of mice and protection by quinidine. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 245 (1–2), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022808224917

- Klatt, P.; Cacho, J.; Crespo, M. D.; Herrera, E.; Ramos, P. Nitric oxide inhibits isoproterenol-stimulated adipocyte lipolysis through oxidative inactivation of the β-agonist. Biochem. J. 2000, 351 (2), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3510485

- Spickett, C. M.; Pitt, A. R. Modification of proteins by reactive lipid oxidation products and biochemical effects of lipoxidation. Essays Biochem. 2019, 64 (1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1042/ebc20190058

- Ulla, A.; Mohamed, M. K.; Sikder, B.; Rahman, A. T.; Sumi, F. A.; Hossain, M.; Reza, H. M.; Rahman, G. M. S.; Alam, M. A. Coenzyme Q10 prevents oxidative stress and fibrosis in isoprenaline induced cardiac remodeling in aged rats. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 18 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-017-0136-7

- Xiao, H.; Li, H.; Wang, J.-J.; Zhang, J.-S.; Shen, J.; An, X.-B.; Zhang, C.-C.; Wu, J.-M.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Yu, H.-Y.; Deng, X.-N.; Li, Z.-J.; Xu, M.; Lu, Z.-Z.; Du, J.; Gao, W.; Zhang, A.-H.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y. IL-18 cleavage triggers cardiac inflammation and fibrosis upon β-adrenergic insult. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 39 (1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx261

- Wu, X.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Guo, F. Pin1 facilitates isoproterenol induced cardiac fibrosis and collagen deposition by promoting oxidative stress and activating the MEK1/2 ERK1/2 signal transduction pathway in rats. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2017.3354

- Ramos-Tovar, E.; Muriel, P. Molecular Mechanisms That Link Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in the Liver. Antioxidants 2020, 9 (12), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121279

- Li, L.; Lu, M.; Peng, Y.; Huang, J.; Tang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Hong, X.; He, M.; Fu, H.; Liu, R.; Hou, F. F.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y. Oxidatively stressed extracellular microenvironment drives fibroblast activation and kidney fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102868

- Jin, B.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, P.; Pan, T.; Guo, B.; Chen, T.; Li, H. Loss of MEN1 leads to renal fibrosis and decreases HGF‐Adamts5 pathway activity via an epigenetic mechanism. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12 (8). https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.982

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Pu, S.; Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Ameliorative Effects of Arctigenin on Pulmonary Fibrosis Induced by Bleomycin via the Antioxidant Activity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2022, 2022 (1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3541731

- Szász, C.; Pap, D.; Szebeni, B.; Bokrossy, P.; Őrfi, L.; Szabó, A. J.; Vannay, Á.; Veres-Székely, A. Optimization of Sirius Red-Based Microplate Assay to Investigate Collagen Production In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24 (24), 17435. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242417435

Author Affiliation

1Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Department of Pharmacy, University of Asia Pacific, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3School of Pharmacy, Brac University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4BCSIR Laboratories, Bangladesh Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR), Dhaka, Bangladesh

ARTICLE INFO

Dr. Anayet Ullah, Assistant Professor, Tokoshuba University, Japan

.jpg)