Abstract

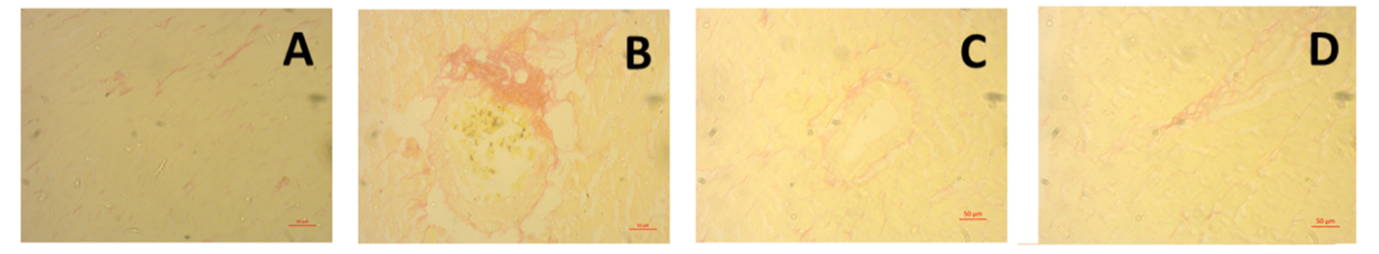

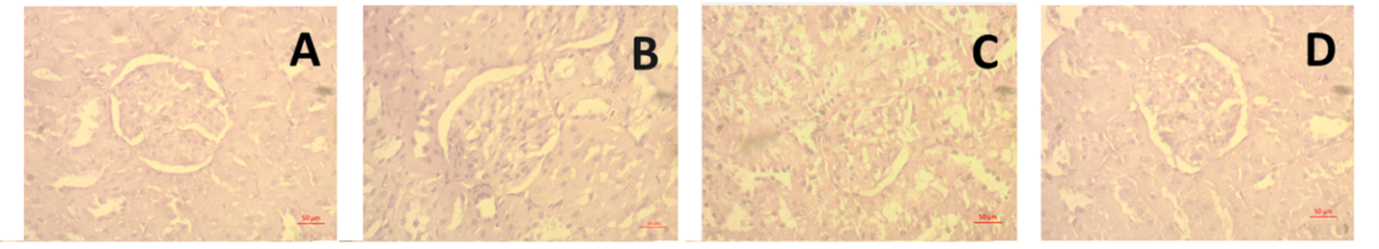

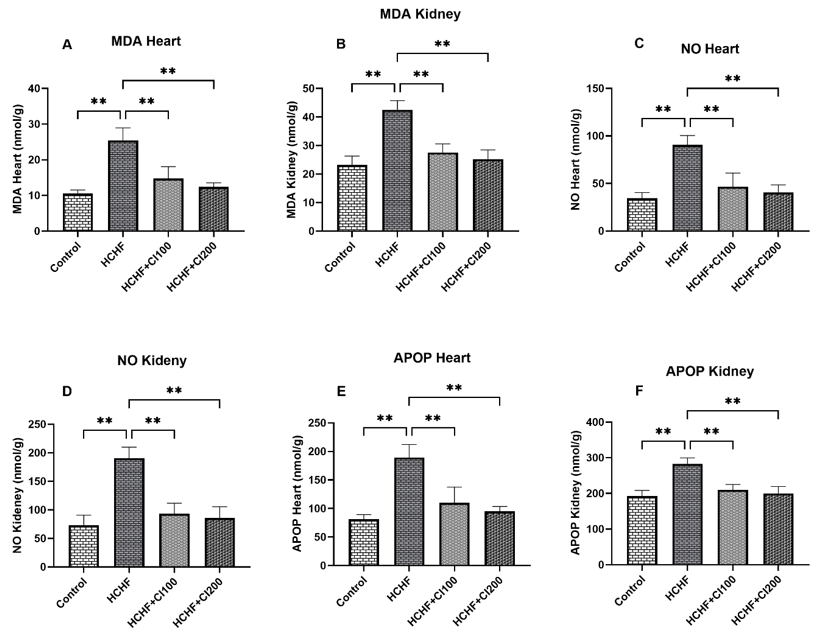

Obesity is a chronic metabolic disorder that is closely related to cardiovascular and renal dysfunctions due to oxidative stress, inflammation, and lipid abnormalities. This study aimed to investigate the cardioprotective and renoprotective effects of ethanolic leaf extract of Coccinia grandis (CI) on high carbohydrate, high fat (HCHF) diet-induced obese Wistar rats. Twenty-four male rats were divided into four groups: Control, HCHF, HCHF + CI100 (100 mg/kg), and HCHF + CI200 (200 mg/kg), and treated orally for 56 days. Biochemical, oxidative stress, and antioxidant enzyme parameters were evaluated in plasma, heart, and kidney tissues, followed by histological analysis. The HCHF diet significantly increased body weight and organ weights, LDL, CK-MB, uric acid, creatinine, MDA, MPO, and NO levels, while decreasing catalase and SOD activity. Treatment with C. grandis extract at both doses significantly reversed these alterations by restoring antioxidant enzyme activity and reducing lipid peroxidation and inflammatory markers. Histological studies showed a marked decrease in fibrosis, collagen deposition, and inflammatory cell infiltration in cardiac and renal tissues of C. grandis-treated groups, with higher doses providing greater protection. These protective effects are attributed to the antioxidant and phenolic constituents of C. grandis, which counter oxidative stress-mediated damage. Overall, C. grandis ethanolic extract demonstrated potent therapeutic potential against diet-induced cardiorenal injury by improving lipid metabolism, oxidative balance, and tissue integrity. These findings suggest the promising application of C. grandis in the management of metabolic syndrome and obesity-related complications.

Cite

- MLA: Shahnaz Siddiqua, Sungida Sharmin, Tanjila Jalal, Faiza Hamid Jyoti, Mehzabin Rahman,Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Nabila Alam, Karima Boshra, Nusrat Subhan, Md Ashraful Alam. "Evaluation of Coccinia grandis Extract on Cardiac and Kidney Dysfunction in High-Carbohydrate High-Fat Diet-Feeding Rats ." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3.1 (2025): 01–19.

- APA: Shahnaz Siddiqua, Sungida Sharmin, Tanjila Jalal, Faiza Hamid Jyoti, Mehzabin Rahman,Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Nabila Alam, Karima Boshra, Nusrat Subhan, Md Ashraful Alam, (2025). Evaluation of Coccinia grandis Extract on Cardiac and Kidney Dysfunction in High-Carbohydrate High-Fat Diet-Feeding Rats . J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), 01–19.

- Chicago: Shahnaz Siddiqua, Sungida Sharmin, Tanjila Jalal, Faiza Hamid Jyoti, Mehzabin Rahman,Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Nabila Alam, Karima Boshra, Nusrat Subhan, Md Ashraful Alam. "Evaluation of Coccinia grandis Extract on Cardiac and Kidney Dysfunction in High-Carbohydrate High-Fat Diet-Feeding Rats ." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3, no. 1 (2025): 01–19.

- Harvard: Shahnaz Siddiqua, Sungida Sharmin, Tanjila Jalal, Faiza Hamid Jyoti, Mehzabin Rahman,Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Nabila Alam, Karima Boshra, Nusrat Subhan, Md Ashraful Alam, 2025. Evaluation of Coccinia grandis Extract on Cardiac and Kidney Dysfunction in High-Carbohydrate High-Fat Diet-Feeding Rats . J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), pp.01–19.

- Vancouver: Shahnaz Siddiqua, Sungida Sharmin, Tanjila Jalal, Faiza Hamid Jyoti, Mehzabin Rahman,Md. Tareq Chowdhury, Nabila Alam, Karima Boshra, Nusrat Subhan, Md Ashraful Alam. Evaluation of Coccinia grandis Extract on Cardiac and Kidney Dysfunction in High-Carbohydrate High-Fat Diet-Feeding Rats . J. Bio. Exp. Pharm. 2025;3(1):01–19.

Keywords

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Method

3. Result

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

In this study it is revealed that in high carbohydrate high fat diet ethanol extract of Coccinia grandis (CI) was used which actually retained antioxidant activity. As high carbohydrate high fat diet was administered it actually caused cardiac fibrosis and renal damage which was restored by the ethanolic extract of Coccinia grandis (CI), consisting of phenolic compounds. With the treatment of Coccinia grandis (CI) ethanolic extract, antioxidant enzyme activity was improved in catalase and SOD. Although the specific chemical compounds present in Coccinia grandis responsible for these protective effects were not identified, our findings can suggest that it possesses notable therapeutic potential against oxidative damage associated with metabolic syndrome and hypercholesterolemia, opening promising windows for future clinical applications for our plant in the management of metabolic and cardiovascular disorders.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization, MAA and NS; methodology, SS, SS and NA; software, MTC and KB; validation, MR, FHJ, and TJ; formal analysis, MR, MAA, and NS; investigation, SS, SS, MTC, NA and KB; resources, MR, NA and KB; data curation, MAA and NS; writing—original draft preparation, SS, TJ, MR, KB; writing—review and editing, FHJ, MTC, NA, KB; visualization, MAA, NS; supervision, MAA and NS project administration, MAA; funding acquisition, MAA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any internal or external funding from profit and non-profit organization.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable (N/A)

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors are gratefully acknowledging the logistic support from the department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Melson, E.; Ashraf, U.; Papamargaritis, D.; and Davies, M.J. What is the pipeline for future medications for obesity? Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49(3), 433-451. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01473-y

- Bovet, P.; Farpour-Lambert, N.; Banatvala, N.; and Baur, L. Obesity: Burden, epidemiology and priority interventions. In Noncommunicable Diseases; Routledge: 2023; pp 74-82. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003306689-12

- Bray, G.A. Medical Consequences of Obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89(6), 2583-2589. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0535

- Budnik, A.; Henneberg, M. Worldwide Increase of Obesity Is Related to the Reduced Opportunity for Natural Selection. PLoS One 2017, 12(1), e0170098. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170098

- Henneberg, M.; Ulijaszek, S.J. Body frame dimensions are related to obesity and fatness: Lean trunk size, skinfolds, and body mass index. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2010, 22(1), 83-91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20957

- Lucas, T.; Henneberg, M. Body frame variation and adiposity in development, a mixed-longitudinal study of "Cape Coloured" children. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2014, 26(2), 151-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22494

- Bozkurt, B.; Ahmad, T.; Alexander, K.M.; Baker, W.L.; Bosak, K.; Breathett, K.; Fonarow, G.C.; Heidenreich, P.; Ho, J.E.; Hsich, E.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Jones, L.M.; Khan, S.S.; Khazanie, P.; Koelling, T.; Krumholz, H.M.; Khush, K.K.; Lee, C.; Morris, A.A.; Page, R.L. II; Pandey, A.; Piano, M.R.; Stehlik, J.; Stevenson, L.W.; Teerlink, J.R.; Vaduganathan, M.; and Ziaeian, B. Heart Failure Epidemiology and Outcomes Statistics: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29(10), 1412-1451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.07.006

- Laule, C.; Rahmouni, K. Leptin and Associated Neural Pathways Underlying Obesity-Induced Hypertension. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15(1), e8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cph4.8

- Zhang, Z.; Dalan, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.W.; Chew, N.W.; Poh, K.K.; Tan, R.S.; Soong, T.W.; Dai, Y.; Ye, L.; and Chen, X. Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Nanomedicine for the Treatment of Ischemic Heart Disease. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34(35), 2202169. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202202169

- Gong, G.; Wan, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; and Yin, J. Management of ROS and Regulatory Cell Death in Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67(5), 1765-1783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12033-024-01173-y

- Aladağ, N.; Asoğlu, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Asoğlu, E.; Derin, A.R.; Demir, C.; and Demir, H. Oxidants and antioxidants in myocardial infarction (MI): Investigation of ischemia modified albumin, malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase and catalase in individuals diagnosed with ST elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI). J. Med. Biochem. 2021, 40(3), 286-294. https://doi.org/10.5937/jomb0-28879

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, H.; and Wang, L. Ferroptosis and Lipid Metabolism in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25(5), 149. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2505149

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, H.; Han, M.; Ren, X.; Gang, X.; and Wang, G. Obesity and chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 324(1), E24-E41. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00179.2022

- Dousdampanis, P.; Aggeletopoulou, I.; and Mouzaki, A. The role of M1/M2 macrophage polarization in the pathogenesis of obesity-related kidney disease and related pathologies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1534823

- Koyagura, N.; Kumar, V.H.; and Shanmugam, C. Anti-diabetic and hypolipidemic effect of Coccinia grandis in glucocorticoid induced insulin resistance. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2021, 14(1), 133-140. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2107

- Siddiqua, S.; Jyoti, F.H.; Saffoon, N.; Miah, P.; Lasker, S.; Hossain, H.; Akter, R.; Ahmed, M.I.; and Alam, M.A. Ethanolic extract of Coccinia grandis prevented glucose intolerance, hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in high fat diet fed rats. Phytomedicine Plus 2021, 1(4), 100046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100046

- Toha, I.W.; Hasan, S.M.F.; Islam, S.; Ahmed, M.H.; Nobe, N.; Tasnim, S.; Shakil, F.A.; and Chowdhury, M.M. Elucidation of Anti-hyperlipidemic Activity of 70% Ethanolic Extract of Coccinia grandis on High Fat-induced Hyperlipidaemic Wister Albino Rat Model. J. Complement. Altern. Med. Res. 2025, 26(3), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.9734/jocamr/2025/v26i3638

- Pattanayak, S.P.; and Sunita, P. In vivo antitussive activity of Coccinia grandis against irritant aerosol and sulfur dioxide-induced cough model in rodents. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2009, 4(2), 84-87. https://doi.org/10.3329/bjp.v4i2.1537

- Banerjee, A.; Roy, J.; Sarkar, D.; Shil, A.; Das, D.; Seal, T.; Mukherjee, S.; and Maji, B.K. The therapeutic role of Coccinia grandis in flavor-enhancing high-lipid diet-induced chronic kidney disease: a dual role of NF-kB and TGF-β/smad in renal fibrosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52(1), 798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-025-10798-4

- Venkateswaran, S.; and Pari, L. Effect of Coccinia grandis on blood glucose, insulin and key hepatic enzymes in experimental diabetes. Pharm. Biol. 2002, 40(3), 165-170. https://doi.org/10.1076/phbi.40.3.165.5836

- Basavarajappa, G.M.; Nanjundan, P.K.; Alabdulsalam, A.; Asif, A.H.; Shekharappa, H.T.; Anwer, M.K.; and Nagaraja, S. Improved renoprotection in diabetes with combination therapy of Coccinia grandis leaf extract and low-dose pioglitazone. Separations 2020, 7(4), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations7040058

- Chinni, S.V.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Anbu, P.; Fuloria, N.K.; Fuloria, S.; Mariappan, P.; Krusnamurthy, K.; Reddy, L.V.; Ramachawolran, G.; Sreeramanan, S.; and Samuggam, S. Characterization and antibacterial response of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using an ethanolic extract of Coccinia grandis leaves. Crystals 2021, 11(2), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst11020097

- Mirza, A.; Rahman, N.; Sornaker, P.; Akramuddaula, K.; Sarif, S.; Siddiqua, S.; Mitu, K.F.; Jahan, I.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; and Alam, A. Evaluation of Terminalia arjuna Bark Powder Supplementation on Isoprenaline-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Heart of Long Evans Rats, Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of This Old Medicinal Plant. J. Med. Nat. Prod. 2024, 1(1), 100004. https://doi.org/10.53941/jmnp.2024.100004

- Ohkawa, H.; Ohishi, N.; and Yagi, K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal. Biochem. 1979, 95(2), 351-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3

- Banerjee, A.; Mukherjee, S.; and Maji, B.K. Efficacy of Coccinia grandis against monosodium glutamate induced hepato-cardiac anomalies by inhibiting NF-kB and caspase 3 mediated signalling in rat model. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40(11), 1825-1851. https://doi.org/10.1177/09603271211010895

- Shuvo, A.U.H.; Alimullah, M.; Jahan, I.; Mitu, K.F.; Rahman, M.J.; Akramuddaula, K.; Khan, F.; Dash, P.R.; Subhan, N.; and Alam, M.A. Evaluation of Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors Febuxostat and Allopurinol on Kidney Dysfunction and Histological Damage in Two-Kidney, One-Clip (2K1C) Rats. Scientifica 2025, 2025(1), 7932075. https://doi.org/10.1155/sci5/7932075

- Wilson, P.W.F.; D'Agostino, R.B.; Sullivan, L.; Parise, H.; and Kannel, W.B. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002, 162(16), 1867-1872. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867

- Lu, Y.; Hajifathalian, K.; Ezzati, M.; Woodward, M.; Rimm, E.B.; and Danaei, G. Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1.8 million participants. Lancet 2014, 383(9921), 970-983. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61836-X

- Sommariva, E.; Stadiotti, I.; Casella, M.; Catto, V.; Dello Russo, A.; Carbucicchio, C.; Arnaboldi, L.; De Metrio, S.; Milano, G.; Scopece, A.; Casaburo, M.; Andreini, D.; Mushtaq, S.; Conte, E.; and Chiesa, M. Oxidized LDL‐dependent pathway as new pathogenic trigger in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 13(9), e14365. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202114365

- Phimarn, W.; Taengthonglang, C.; and Sungthong, B. Efficacy and safety of Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt on blood glucose and lipid profile: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2024, 13(3), 342-352. https://doi.org/10.34172/jhp.2024.49331

- Suryaningtyas, I.T.; Marasinghe, C.K.; Lee, B.; and Je, J.Y. Oral administration of PIISVYWK and FSVVPSPK peptides attenuates obesity, oxidative stress, and inflammation in high fat diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 136, 109791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2024.109791

- Duan, Y.; Zeng, L.; Zheng, C.; Song, B.; Li, F.; Kong, X.; and Xu, K. Inflammatory links between high fat diets and diseases. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2649. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02649

- Podrez, E.A.; Schmitt, D.; Hoff, H.F.; and Hazen, S.L. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 103(11), 1547-1560. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci5549

- Hazell, L.J.; Stocker, R. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein with hypochlorite causes transformation of the lipoprotein into a high-uptake form for macrophages. Biochem. J. 1993, 290(1), 165-172. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj2900165

- Frangie, C.; and Daher, J. Role of myeloperoxidase in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Biomed. Rep. 2022, 16(6), 53. https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2022.1536

- Podrez, E.A.; Febbraio, M.; Sheibani, N.; Schmitt, D.; Silverstein, R.L.; Hajjar, D.P.; Cohen, P.A.; Frazier, W.A.; Hoff, H.F.; and Hazen, S.L. Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 105(8), 1095-1108. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI8574

- Prem, P.N.; and Kurian, G.A. High-fat diet increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 715693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.715693

- Putra, I.M.W.A.; Fakhrudin, N.; Nurrochmad, A.; and Wahyuono, S. Antidiabetic effect of combined extract of Coccinia grandis and Blumea balsamifera on streptozotocin-nicotinamide induced diabetic rats. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2024, 15(4), 101021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2024.101021

- Aref, M.; Mohamed, D.S.; Hamza, M.F.; and Gomaa, I. Chia seeds ameliorate cardiac disease risk factors via alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation in rats fed high-fat diet. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 2940. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41370-4

- Fouad, G.I. Synergistic anti-atherosclerotic role of combined treatment of omega-3 and co-enzyme Q10 in hypercholesterolemia-induced obese rats. Heliyon 2020, 6(4), e03659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03659

- Wang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Fang, Q.; Zhong, P.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Fu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; and Liang, G. Saturated palmitic acid induces myocardial inflammatory injuries through direct binding to TLR4 accessory protein MD2. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8(1), 13997. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13997

- Banerjee, A.; Das, D.; Paul, R.; Roy, S.; Das, U.; Saha, S.; Dey, S.; Adhikary, A.; Mukherjee, S.; and Maji, B.K. Mechanistic study of attenuation of monosodium glutamate mixed high lipid diet induced systemic damage in rats by Coccinia grandis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 15443. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72076-6

- Zhou, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, X.; Pan, Z.; Jin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; and Ling, W. Resveratrol improves hyperuricemia and ameliorates renal injury by modulating the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16(7), 1086. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16071086

Author Affiliation

1Department of Pharmacy, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

ARTICLE INFO

Dr. Ferdous Khan, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh