Abstract

Cardiorenal complications often arise from oxidative stress which ultimately disrupts the renal structure and function. For the exploration of the therapeutic potential of natural antioxidants, this study examined the effects of Sonneratia apetala (Keora) fruit peel extract in an Isoproterenol (ISO) – induced model of renal injury in rats. The Long Evans rats were grouped as Control, ISO, Control + Keora, and ISO + Keora. ISO (50 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously every third day for two weeks, which produced significant oxidative stress to renal tissues, evidenced by an elevated MDA, NO, AOPP and MPO levels, along with a reduced SOD, CAT and GSH activities, increased plasma creatinine and uric acid concentrations. Oral pretreatment with Keora peel extract (100 mg/kg/day) provided an improved antioxidant enzyme activity, while lowering the oxidative and nitrosative stress markers thus normalizing the renal function indicators. Histopathological changes also backed up these biochemical results, showing a more preserved glomerular morphology and reduced collagen accumulation in the renal tissues of the Keora-treated rats. Overall, Keora fruit peel extract showed a strong renoprotective potential against ISO-induced nephrotoxicity, which suggests that its bioactive constituents may counteract oxidative damage and fibrosis through the enhancement of antioxidant defenses and limiting oxidative injury.

Cite

- MLA: Sultana, S.; Alimullah, M.; Ghosh, H. C.; Jalal, T.; Hossen, M. T.; Joya, A. B.; Akter, A.; Akhter, T.; Alauddin, J.; Subhan, N., Alam, M. A.. "Mangrove Fruit Keora Peel Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in the Kidney of ISO Administered Rats." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3.1 (2025): 89-100.

- APA: Sultana, S.; Alimullah, M.; Ghosh, H. C.; Jalal, T.; Hossen, M. T.; Joya, A. B.; Akter, A.; Akhter, T.; Alauddin, J.; Subhan, N., Alam, M. A., (2025). Mangrove Fruit Keora Peel Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in the Kidney of ISO Administered Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), 89-100.

- Chicago: Sultana, S.; Alimullah, M.; Ghosh, H. C.; Jalal, T.; Hossen, M. T.; Joya, A. B.; Akter, A.; Akhter, T.; Alauddin, J.; Subhan, N., Alam, M. A.. "Mangrove Fruit Keora Peel Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in the Kidney of ISO Administered Rats." J. Bio. Exp. Pharm 3, no. 1 (2025): 89-100.

- Harvard: Sultana, S.; Alimullah, M.; Ghosh, H. C.; Jalal, T.; Hossen, M. T.; Joya, A. B.; Akter, A.; Akhter, T.; Alauddin, J.; Subhan, N., Alam, M. A., 2025. Mangrove Fruit Keora Peel Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in the Kidney of ISO Administered Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm, 3(1), pp.89-100.

- Vancouver: Sultana, S.; Alimullah, M.; Ghosh, H. C.; Jalal, T.; Hossen, M. T.; Joya, A. B.; Akter, A.; Akhter, T.; Alauddin, J.; Subhan, N., Alam, M. A.. Mangrove Fruit Keora Peel Extract Prevents Oxidative Stress and Fibrosis in the Kidney of ISO Administered Rats. J. Bio. Exp. Pharm. 2025;3(1):89-100.

Keywords

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Isoprenaline hydrochloride was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Reagents and standards required for myeloperoxidase (MPO), malondialdehyde (MDA), nitric oxide (NO), and advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP) assays, Catalase (CAT), along with Picrosirius red staining materials, were sourced from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Sigma-Aldrich. standards and associated assay components were procured from SR Group (Delhi, India). Commercial kits for uric acid and creatinine analyses were purchased from DCI Diagnostics (Budapest, Hungary).

2.2 Preparation of Sonneratia apetala Fruits Extracts

The fruits of Keora were sourced from the Mangrove forest Sundarbans, located in Khulna, Bangladesh. After collection, the fruits were oven-dried at 50 °C and finely ground into powder. A total of 500 g of the powdered material was macerated in ethanol within a sealed glass container and stored in a dark environment at ambient temperature for five days, with intermittent shaking. The resulting mixture was filtered to obtain the ethanolic extract. Ethanol was subsequently removed using a rotary evaporator set at 50 °C and 100 rpm, yielding a concentrated crude extract. An identical procedure was employed to prepare the methanolic extract.

2.3 Experimental animals

Twenty-four male Long Evans rats, aged 8–10 weeks and weighing between 180–190 g, were procured from the animal facility of the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, for this study. The animals were housed under standardized laboratory conditions, including a 12-hour light/dark cycle, relative humidity of approximately 55%, and a controlled temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. All procedures adhered to international ethical guidelines outlined by the Council for International Organization of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and the International Council for Laboratory Animal Science (ICLAS). Ethical approval for the experimental protocols was granted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of North South University (Approval No- 2025/OR-NSU/IACUC/0209).

2.4 Experimental design and treatment protocol

The rats were divided into four groups, each group consisting of 6 rats. The groups were as such.

- Control group: For two weeks, the rats in this group were fed chow meals and regular water daily.

- ISO (Isoprenaline) group: For two weeks, the ISO group received subcutaneous injections of isoprenaline at a rate of 50 mg/kg every three days. The ISO group was given isoprenaline along with water and chow food.

- Control + Keora: For two weeks, the rats in this group were given regular water and chow meals treated with Keora fruit peel extract (100 mg/kg of body weight).

- ISO + Keora: For two weeks, the rats in this group were given 50 mg/kg of isoprenaline subcutaneously every three days, along with chow food and water. This group also received a 100 mg/kg of body weight dose of Keora fruit peel extract.

After completion of 14 days of the procedure, the rats were weighed and then sacrificed on the 15th day. Blood was collected and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, with a temperature of 4 °C in order to collect the plasma. Following that, the required organs left and right kidneys, were collected and weighed. The harvested organs, including kidney tissues, were stored for bioassay, and one part of the kidney was stored in neutral buffer formalin for the use of histology staining. The plasma and tissues collected for bioassay were stored at −18 °C preserved for bioassay analysis. A portion of the kidney tissue was fixed in neutral buffered formalin for histological examination. All plasma and tissue samples designated for bioassay were stored at −18 °C until further use.

2.5 Induction of Myocardial Infarction

Rats were given subcutaneous injections of 50 mg/kg of isoproterenol (ISO) hydrochloride, dissolved in physiological solution, to induce an experimental myocardial infarction.

2.6 Determination of Kidney Function via Creatinine and Uric Acid Measurement

Kidney specific marker tests such as creatinine, and uric acid were also performed using plasma following the manufacturer's protocol.

2.7 Preparing a Tissue Sample for Oxidative Stress Marker Evaluation

To separate the supernatant, the heart and kidney tissues were homogenized in 10% phosphate buffer saline (pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. After collecting, the supernatants were utilized in enzymatic and protein analyses.

2.8 Malondialdehyde estimation (MDA)

To detect plasma and heart lipid peroxidation, reactive thiobarbituric acid substances (TBARS) were measured colorimetrically using a previously published technique [14]. Malondialdehyde (MDA), a consequence of lipid peroxidation, is measured using the TBARS test. Samples of plasma and heart tissue were diluted with PBS, 100 µL of glacial acetic acid was added, and the mixture was left for 10 minutes to measure the MDA concentration. After adding 200 µL of TBA (0.37%), the mixture was put in a sealed Eppendorf tube and heated for about fifteen minutes in a hot water bath. After cooling to room temperature, 200 µL of the mixture was put into a 96-well plate, and the absorbance at 535 nm was measured. Using 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane as a reference, an MDA standard curve was created to determine the MDA levels in tissue and plasma samples. The measuring units of plasma and tissue were mmol/mL and mmol/g, respectively.

2.9 Nitric oxide estimation (NO)

Using the earlier technique (Griess reaction), the NO concentration was determined [14]. This procedure involved taking 20 µL samples on a 96-well plate with 80 µL PBS and waiting 10 minutes. The sample mixture was then mixed with 50 µL of 0.1% w/v naphthyl ethylene diamine dihydrochloride (NED) and 50 µL of sulfanilamide solution. The liquid was then made acidic by adding 50 µL of 15% glacial acetic acid. After ten minutes of waiting, the absorbance at 540 nm was measured. The units were expressed as mmol/mL or mmol/g of tissue, and the standard curve was created using NaNO2 as a standard.

2.10 Estimation of Advanced Protein Oxidation Products (APOP)

The aforementioned technique was used to measure the amount of AOPP in tissues and plasma [15]. on order to create an acidic medium, 50 µL of glacial acetic acid (15%) was added to 10 µL samples that had been collected with 90 µL PBS on a 96-well plate. To create a colored complex, 50 µL of potassium iodide (1.16 mM) was then added. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured after two minutes of waiting. The units were expressed as mmol/mL or mmol/g of tissue, with chloramine T serving as the reference.

2.11 Estimation of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

MPO activity was assessed using the previously developed di-anisidine-H2O2-based test technique [16]. This method was modified to function with 96-well plates. 10 µL sample were mixed with 250µL PBS and then 3µL of H2O2 (0.15 mM) were added. After that, 3µL of o-dianisidine solution was added, and the absorbance was taken at 460 nm and reported as MPO activity/mg protein.

2.12 Assessment of the activity of antioxidant enzymes

SOD, catalase, and GSH activities were also measured in the heart and plasma using modified methods that have been previously reported in the literature [17, 18]. To put it briefly, 90 µL of PBS was combined with 10 µL of the sample, and then 100 µL of adrenaline was added. Absorbance was measured at 15-second intervals for 1 minute at 480 nm during 50% adrenaline auto-oxidation. One minute after starting, changes in absorbance at 240 nm were monitored. To measure catalase activity, 10 µL of the sample was combined with 90 µL of PBS, and then 50 µL of H2O2 (5.9 mmol) was added. After mixing 10µL of the sample with 90µL of PBS, 100µL of DTNB reagent (100 mM 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid) was added to measure the GSH activity.

2.13 Histopathological Evaluation

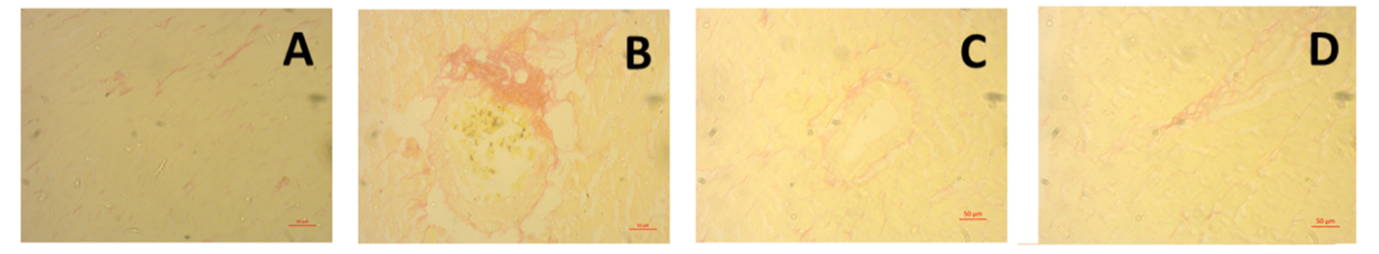

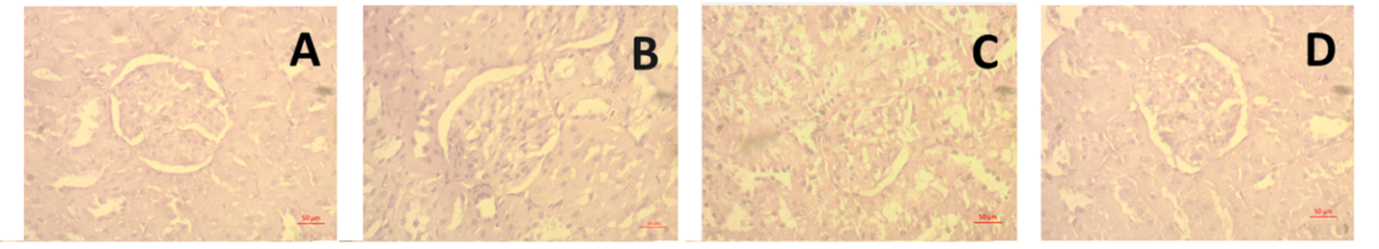

For microscopic examination, excised kidney tissues from experimental rats were initially fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF). The fixed specimens were then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin to prevent air entrapment. Thin sections approximately 5 µm in thickness were prepared using a rotary microtome and mounted onto clean glass slides. These sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to assess inflammatory cell infiltration. Additionally, Picrosirius Red staining was performed to visualize and evaluate fibrotic alterations. All stained slides were imaged and analyzed under a light microscope (Zeiss Axioscope) at 40× magnification.

2.14 Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical evaluations were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10. Group comparisons were conducted via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to identify significant differences among treatment groups. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

3. Results

In Figure 1, the effect of ISO administration and Keora peel extract supplementation on Kidney Wet weight has been shown and it was seen that ISO group showed negligible changes in kidney wet weight compared to the Control group (p = 0.3372). However, the supplementation of Keora peel extract in ISO administered rats showed a significant reduction in kidney weight compared to the ISO only group (p = 0.0041). There was no significant difference between the Control and Control + Keora group in the wet weights of the kidney (p = 0.8800).

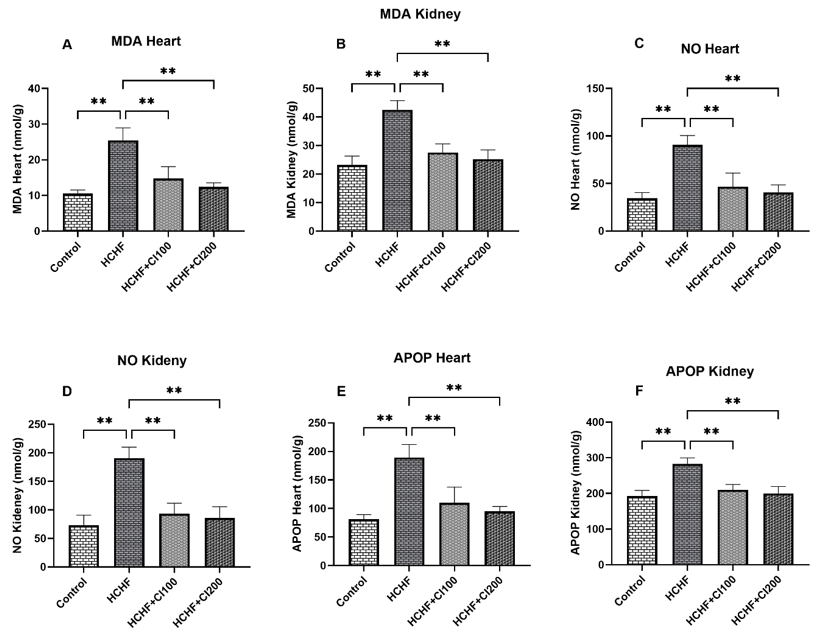

Figure 2 represents the levels of oxidative stress markers in the kidney tissues. From Figure 2A, it can be seen that the concentration of Malondialdehyde (MDA) was significantly increased in the ISO treated group when compared to the Control group (p < 0.0001). Treatment with Keora peel extract in the ISO + Keora group resulted in a significant decrease in MDA concentration when compared to the group treated with ISO only (p < 0.0001). Similarly, in Figure 2B, which represents the Nitric Oxide concentration in the kidney tissues, it was seen that the ISO treated group had a significantly higher concentration of NO compared to the Control group (p < 0.0001). Treatment with Keora peel extract in the ISO + Keora group showed a marked decrease in NO concentration when compared to the ISO administered group (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, in Figure 2C, the level of Advanced Oxidation Protein Products (AOPP) was found to be significantly increased in the ISO administered group when compared to the Control group (p < 0.0001). Keora supplementation to ISO administered rats in the ISO + Keora groups seems to have significantly decreased the AOPP concentration when compared to the ISO group (p < 0.0001). Finally, no significant difference was found between the Control group and the Control + Keora group among all Oxidative Stress markers.

The antioxidant systems in the kidney tissues have been shown in Figure 3. From Figure 3A, it can be seen that the Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was considerably reduced in the ISO group when compared to the Control group (P = 0.0008). Conversely, the ISO + Keora group showed a significant increase in SOD activity when compared to the ISO only group (P = 0.0171). In Figure 3B, the Catalase activity of the ISO group was also significantly reduced when compared to the Control group (P = 0.0014). However, Keora peel extract treatment in the ISO administered group, ISO + Keora, showed a considerable increase in the Catalase activity levels when compared to the ISO only group (P = 0.0068). For reduced Glutathione (GSH) represented in Figure 3C, the ISO group had significantly diminished levels when compared with the Control group (P < 0.0001). ISO + Keora group exhibited a significant increase in the GSH levels when compared to the ISO only group (P = 0.0002). No statistically significant difference was found between the Control group and the Control + Keora group for any of the tested Kidney Antioxidant Activities

The results for Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the kidney have been represented in Figure 4A, which shows that ISO had significantly increased the MPO activity in the kidney tissues when compared to the Control group (P < 0.0001). Treatment with Keora in the ISO + Keora group drastically reduced the elevated levels when compared to the ISO only treated group (P < 0.0001). Figure 4B representing the Uric Acid concentration in plasma also showed a significantly increased concentration of Uric Acid in the ISO group when compared with the Control group (P < 0.0001). ISO + Keora-treated group showed a significant decrease in the Uric Acid concentration when compared with the group only administered with ISO (P < 0.0001). The Creatinine Concentration in plasma, represented in Figure 4C, was highly elevated in the ISO group when compared with the Control group (P < 0.0001). The addition of Keora peel extract to ISO administered treatment group, ISO + Keora, exhibited a significantly reduced Creatinine concentration (P < 0.0001) when compared with the ISO only group. No significant difference was observed between the Control and Control + Keora groups across MPO activity, Uric Acid, and Creatinine Levels.

4. Discussion

The study's key discovery is that Keora extracts reduced oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation while increasing antioxidant enzymes, therefore attenuating ISO-induced fibrosis in renal tissue. Additionally, ISO-induced histological alterations were reduced by the extract. The β-adrenergic receptors are expressed by juxtaglomerular granular cells, vascular smooth muscle cells from arteries, and kidney tubules (proximal and distal tubular cells). Norepinephrine sends adrenergic signals to these tissues, which control fluid balance and renal hemodynamics [19]. Cellular macromolecules and membrane phospholipids are oxidized in turn by the excess ROS. These free radicals, which are generated in tissues, can damage and necrotize cells by attacking the lipid layers of the cell membrane [14]. Increased MDA levels and oxidative damage to lipid membranes result from ISO's imbalance between ROS generation and antioxidant defenses. Increased MDA levels signify oxidative stress-induced renal cell membrane damage, which leads to cellular malfunction and apoptosis [20]. The amounts of lipid hydroperoxides and TBARS in the kidney tissue were considerably decreased by pretreatment with Keora fruit peel. This result demonstrated Keora's ability to prevent lipid peroxidation. The development of renal dysfunction was also triggered by the generation of free radicals in the tissues. One common indicator of oxidative stress is Nitric oxide, which is converted to nitrite via oxidation. Normal endothelium and vascular activity trigger the generation of NO, which is known to rise under inflammatory conditions and promote cell death [21]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase, or iNOS, is involved in the creation of NO in vivo. When oxidative stress is present, iNOS expression rises, producing too much NO, which can easily cause lipid peroxidation [22]. By generating excessive quantities of NO, which combine with superoxide to generate peroxinitrite, iNOS plays a crucial role in mediating nitro-oxidative stress [23]. Peroxynitrite, which is more reactive than superoxide and can cause irreversible cellular damage, is often produced over time from nitric oxide [24]. One significant indicator of oxidative stress in tissues is advanced oxidation protein product (AOPP). Plasma proteins may react with chlorine-free radicals to produce AOPP as a result of elevated oxidative stress [25]. The current study found that ISO rats had higher levels of APOP in their kidney tissues than the control group, which Keora helped to reduce.

Some free radicals may still be present in tissues because of the antioxidants' defense mechanism. SOD, CAT, and GSH are examples of free radical scavenging enzymes that can help mitigate oxidative and nitrosative stress. Furthermore, ISO-induced myocardial injury also results in a decrease in endogenous antioxidants [26]. H2O2 is primarily converted to water by catalase, while superoxide radicals are scavenged by SOD to produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [27]. Cellular defense against reactive free radicals and other oxidant species is largely dependent on the glutathione antioxidant system. GSH, a cellular tripeptide, neutralizes free radicals to prevent peroxidative damage [28]. Reduced GSH levels in rats given isoproterenol may result from its increased use to shield proteins with SH groups from free radical damage [29]. Glutathione (GSH) and antiperoxidative enzyme (CAT & SOD) activities were significantly reduced in the kidney tissue of the rats given ISO; however, these antioxidant activities were enhanced after pretreatment with Keora fruit peel extract.

MPO is an indicator of oxidative damage and inflammation. It is the most prevalent pro-inflammatory biomarker found in neutrophilic granulocytes [30]. Prior studies found that ISO-induced kidney dysfunction in animals was associated with noticeably elevated MPO levels and activity [31]. MPO makes H2O2 more reactive by generating RNS, free radicals, and hypochlorous acid. In acute MI, MPO and all of these products encourage lipid peroxidation, protein nitration, and further oxidative alterations [30]. Our study found a significantly elevated level of MPO in the kidney tissue of ISO-administered rats, which was significantly reduced by the Keora fruit extract treatment. This might be due to the Reno protective effect of Keora.

We also verified in this investigation that elevated kidney injury indicators, such as elevated plasma levels of urea and creatinine, which indicate lower glomerular filtration rates, were linked to isoprenaline-induced kidney damage. Uric acid is the final byproduct of purine metabolism and a waste product that comes from food and diet [32]. Uric acid is primarily controlled by xanthine oxidoreductase, which transforms hypoxanthine into xanthine and xanthine into uric acid [33]. Elevated blood uric acid levels can raise the risk of heart and kidney disease. If the kidneys are unable to eliminate uric acid from our bodies adequately, it can accumulate in the blood and may be a sign of renal dysfunction [34, 35]. In our study, we found that the ISO-administered disease group showed a high level of plasma uric acid compared to the normal control group of rats. The treatment with Keora fruit significantly reduced the elevated uric acid present in the plasma in the ISO-administered rats. This may suggest that the treatment of S. apetala fruit enhanced the renal function.

Another commonly used biomarker for kidney function and estimation of glomerular filtration rate is creatinine [36]. When muscles contract, creatinine is generated from the muscle tissue. It is a waste product from metabolism that is easily removed by the kidneys. Therefore, renal insufficiency, which is manifested as a decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate, is linked to extremely high levels of plasma creatinine [37]. Our result displayed a significantly high plasma creatinine level in the ISO-administered group, which indicates renal insufficiency. The high plasma creatinine level was reduced significantly in the treatment group of ISO-administered rats. This might also indicate the ameliorating effect of the kidney function of the Keora fruit. In addition, the Control+Keora treatment group showed similar creatinine levels, which may prove that there was no kidney toxicity in the given dose of Keora fruit extract.

Lastly, kidney samples were examined histopathologically. Hematoxylin and Eosin were used to stain the kidney sections. Rats given ISO developed aberrant glomerular structure and renal necrosis, which are avoided by treating them with Keora fruit peel. The biochemical investigations that are connected to renal inflammation and oxidative stress corroborate these histological alterations. Collagen deposition in kidney slices is determined by another staining method, such as Sirius red staining. Collagen deposition was observed to be much elevated in the rats given ISO, but it was decreased when Keora fruit was given.

5. Conclusions

The current investigation indicated that pretreatment with Keora fruit peel lowered oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation following ISO-induced renal damage. It enhanced antioxidant enzymes, which lowered the plasma levels of creatinine and uric acid. The reno-protective effects of Keora fruit peel may be related to the presence of antioxidant ingredients and the mitigation of oxidative stress. However, the identification of precise mechanisms of action needs more exploration.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization, MAA and NS; methodology, SS, MA, TJ, MTH, ABJ, and HCG; software, MA and SS; validation, MAA, NS, and HCG; formal analysis, MA, ABJ, AA, TA, JA and NS; investigation, SS, ATH, ABJ, AK, TA and JA; resources, TA and JA; data curation, MAA and MA; writing—original draft preparation, SS, HCG, TJ; writing—review and editing, MA, TA and JA; visualization, MAA, NS; supervision, MAA and NS project administration, MAA; funding acquisition, MAA. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any internal or external funding from profit or non-profit organizations.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zoccali, C.; Mark, P. B.; Sarafidis, P.; Agarwal, R.; Adamczak, M.; Bueno de Oliveira, R.; Massy, Z. A.; Kotanko, P.; Ferro, C. J.; Wanner, C.; Burnier, M.; Vanholder, R.; Mallamaci, F.; Wiecek, A. Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol, 2023 19(11), 733–746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-023-00747-4

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circulation 2023, 143(11), 1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.050686

- Ravarotto, V.; Bertoldi, G.; Innico, G.; Gobbi, L.; Calò, L. A. The Pivotal Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular-Renal Remodeling in Kidney Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10(7), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10071041

- Kenneally, L. F.; Lorenzo, M.; Romero-González, G.; Cobo, M.; Núñez, G.; Górriz, J. L.; Barrios, A. G.; Fudim, M.; de la Espriella, R.; Núñez, J. Kidney function changes in acute heart failure: a practical approach to interpretation and management. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16(10), 1587–1599. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfad031

- Barbagallo, C. M.; Cefalù, A. B.; Giammanco, A.; Noto, D.; Caldarella, R.; Ciaccio, M.; Averna, M. R.; Nardi, E. Lipoprotein Abnormalities in Chronic Kidney Disease and Renal Transplantation. Life 2021, 11(4), 315. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11040315

- Schuett, K.; Marx, N.; Lehrke, M. The Cardio-Kidney Patient: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics and Therapy. Circ. Res. 2023, 132(8), 902–914. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.122.321748

- allianou, N. G.; Mitesh, S.; Gkogkou, A.; Geladari, E. Chronic Kidney Disease and Cardiovascular Disease: Is there Any Relationship? Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2018, 15(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403x14666180711124825

- Collins, A. J. Cardiovascular Mortality in End-Stage Renal Disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 2003, 325(4), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-200304000-00002

- Yasmine, S.; Proma, R. Z.; Uddin, Md. R.; Rahman, M. S.; Islam, Md. H.; Mansur, M. A. A.; Jamal, A. S. I. M.; Yousuf, A.; Mustak, Md. H.; Kamruzzaman, S.; Siddiqi, M. M. A. Exploring the multifaceted roles of Sonneratia apetala and Nipa fruticans in coastal habitat restoration and bioactive properties discovery. Phytomedicine Plus 2025, 5(1), 100687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phyplu.2024.100687

- Uddin, M. R.; Akhter, F.; Abedin, M. J.; Shaikh, M. A. A.; Al Mansur, M. A.; Saydur Rahman, M.; Molla Jamal, A. S. I.; Akbor, M. A.; Hossain, M. H.; Sharmin, S.; Idris, A. M.; Khandaker, M. U. Comprehensive analysis of phytochemical profiling, cytotoxic and antioxidant potentials, and identification of bioactive constituents in methanoic extracts of Sonneratia apetala fruit. Heliyon 2024, 10(13), e33507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33507

- Hossain, S. J.; Basar, M. H.; Rokeya, B.; Arif, K. M. T.; Sultana, M. S.; Rahman, M. H. Evaluation of antioxidant, antidiabetic and antibacterial activities of the fruit of Sonneratia apetala (Buch.-Ham.). Oriental Pharmacy and Experimental Medicine 2012, 13(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13596-012-0064-4

- Hossain, S. J.; Iftekharuzzaman, M.; Haque, M. A.; Saha, B.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Rahman, M. M.; Hossain, H. Nutrient Compositions, Antioxidant Activity, and Common Phenolics ofSonneratia apetala(Buch.-Ham.) Fruit. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 19(5), 1080–1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2015.1055361

- Liu, J.; Luo, D.; Wu, Y.; Gao, C.; Lin, G.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, J.; Su, Z. The Protective Effect of Sonneratia apetala Fruit Extract on Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, 2019, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6919834

- Shuvo, A. U. H.; Alimullah, M.; Jahan, I.; Mitu, K. F.; Rahman, M. J.; Akramuddaula, K.; Khan, F.; Dash, P. R.; Subhan, N.; Alam, M. A. Evaluation of Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors Febuxostat and Allopurinol on Kidney Dysfunction and Histological Damage in Two‐Kidney, One‐Clip (2K1C) Rats. Scientifica 2025, 2025(1). https://doi.org/10.1155/sci5/7932075

- Alimullah, M.; Rahman, N.; Sornaker, P.; Akramuddaula, K.; Sarif, S.; Siddiqua, S.; Mitu, K. F.; Jahan, I.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, Md. A. Evaluation of Terminalia arjuna Bark Powder Supplementation on Isoprenaline-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Heart of Long Evans Rats, Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of This Old Medicinal Plant. Journal of Medicinal Natural Products 2024, 100004. https://doi.org/10.53941/jmnp.2024.100004

- Jahan, I.; Shuvo, A. U. H.; Alimullah, M.; Rahman, A. S. M. N.; Siddiqua, S.; Rafia, S.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, K. S.; Hossain, H.; Akramuddaula, K.; Alam, M. A.; Subhan, N. Purple potato extract modulates fat metabolizing genes expression, prevents oxidative stress, hepatic steatosis, and attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity in male rats. PLOS ONE 2025, 20(4), e0318162. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0318162

- Alimullah, M.; Jahan, I.; Rahman, Md. M.; Khan, F.; Shahin Ahmed, K.; Hossain, Md. H.; Arabnozari, H.; Alam, Md. A.; Sarker, S. D.; Nahar, L.; Subhan, N. Camellia sinensis powder rich in epicatechin and polyphenols attenuates isoprenaline induced cardiac injury by activating the Nrf2 HO1 antioxidant pathway in rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08720-w

- Jahan, I.; Hassan, S. H.; Alimullah, M.; Haque, A. U.; Fakruddin, M.; Subhan, N.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, K. S.; Akramuddaula, K.; Hossain, H.; Alam, M. A. Evaluation of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) powder supplementation on metabolic syndrome, oxidative stress and inflammation in high fat diet fed rats. Pharmacological Research - Natural Products 2024, 5, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prenap.2024.100116

- Yasmin, T.; Alimullah, M.; Rahman, M. J.; Sultana, S.; Siddiqua, S.; Jahan, I.; Rana, S.; Subhan, N.; Khan, F.; Alam, M. A.; Akhter, N. (2025). Therapeutic role of resveratrol treatment on inflammation and oxidative stress-mediated renal and cardiac dysfunction in isoproterenol (ISO) administered ovariectomized female Long Evans rats. Biomed. pharmacother. 2025, 192, 118571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2025.118571

- Alfwuaires, M. Ursolic acid alleviates isoproterenol-induced kidney injury in mice by suppressing inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress via the PI3K/Akt signaling. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2025, 15(8), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjtb.apjtb_767_24

- Moke, E. G.; Asiwe, J. N.; Ben-Azu, B.; Chidebe, E. O.; Demaki, W. E.; Umukoro, E. K.; Oritsemuelebi, B.; Daubry, T. M. E.; Nwogueze, B. C.; Ahama, E. E.; Erhirhie, E. O.; Oyovwi, O. M. Co-enzyme-Q10 and taurine abate isoprenaline-mediated hepatorenal dysregulations and oxidative stress in rats. Clinical Nutrition Open Science 2024, 57, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutos.2024.07.008

- Huang, H., et al., Protective effect of scutellarin on myocardial infarction induced by isoprenaline in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2018. 21(3), 267-276.

- Hasan, R.; Lasker, S.; Hasan, A.; Zerin, F.; Zamila, M.; Chowdhury, F. I.; Nayan, S. I.; Rahman, Md. M.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, Md. A. Canagliflozin attenuates isoprenaline-induced cardiac oxidative stress by stimulating multiple antioxidant and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Sci. REP. 2020, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71449-1

- Selim, S.; Akter, N.; Nayan, S. I.; Chowdhury, F. I.; Saffoon, N.; Khan, F.; Ahmed, K. S.; Ahmed, M. I.; Hossain, M. M.; Alam, M. A. Flacourtia indica fruit extract modulated antioxidant gene expression, prevented oxidative stress and ameliorated kidney dysfunction in isoprenaline administered rats. Biochem Biophys Rep 2021, 26, 101012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.101012

- Rahman, Md. M.; Ferdous, K. U.; Roy, S.; Nitul, I. A.; Mamun, F.; Hossain, Md. H.; Subhan, N.; Alam, M. A.; Haque, Md. A. (2020). Polyphenolic compounds of amla prevent oxidative stress and fibrosis in the kidney and heart of 2K1C rats. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8(7), 3578–3589. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1640

- Rahman, Md. M.; Alimullah, M.; Yasmin, T.; Akhter, N.; Ahmed, I.; Khan, F.; Saha, M.; Halim, M. A.; Subhan, N.; Haque, Md. A.; Alam, Md. A. Cardioprotective action of apocynin in isoproterenol‐induced cardiac damage is mediated through Nrf‐2/HO‐1 signaling pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12(11), 9108–9122. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.4465

- Jahan, I.; Saha, P.; Eysha Chisty, T. T.; Mitu, K. F.; Chowdhury, F. I.; Ahmed, K. S.; Hossain, H.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, Md. A. (2023). Crataeva nurvala Bark (Capparidaceae) Extract Modulates Oxidative Stress‐Related Gene Expression, Restores Antioxidant Enzymes, and Prevents Oxidative Stress in the Kidney and Heart of 2K1C Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2023, 2023(1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4720727

- Ganesan, B.; Buddhan, S.; Anandan, R.; Sivakumar, R.; AnbinEzhilan, R. (2009). Antioxidant defense of betaine against isoprenaline-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2009, 37(3), 1319–1327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-009-9508-4

- Lalitha, G.; Poornima, P.; Archanah, A.; Padma, V. V. (2012). Protective Effect of Neferine Against Isoproterenol-Induced Cardiac Toxicity. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 13(2), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-012-9196-5

- Lin, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, C. The Roles of Neutrophil-Derived Myeloperoxidase (MPO) in Diseases: The New Progress. Antioxidants 2024, 13(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13010132

- Chisty, T. T. E.; Sarif, S.; Jahan, I.; Ismail, I. N.; Chowdhury, F. I.; Siddiqua, S.; Yasmin, T.; Islam, M. N.; Khan, F.; Subhan, N.; Alam, M. A. Protective effects of l-carnitine on isoprenaline -induced heart and kidney dysfunctions: Modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress-related gene expression in rats. Heliyon 2024, 10(3), e25057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25057

- Jakše, B.; Jakše, B.; Pajek, M.; Pajek, J. Uric Acid and Plant-Based Nutrition. Nutrients 2019, 11(8), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081736

- Battelli, M. G.; Bortolotti, M.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A. The role of xanthine oxidoreductase and uric acid in metabolic syndrome. BBA Molecular Basis of Disease 2018, 1864(8), 2557–2565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.05.003

- Obermayr, R. P.; Temml, C.; Gutjahr, G.; Knechtelsdorfer, M.; Oberbauer, R.; Klauser-Braun, R. Elevated Uric Acid Increases the Risk for Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 19(12), 2407–2413. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2008010080

- Feig, D. I.; Kang, D.-H.; Johnson, R. J. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med 2008, 359(17), 1811-21. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra0800885

- Ebert, N.; Schaeffner, E. New biomarkers for estimating glomerular filtration rate. J Lab Precis Med 2018, 3, 75–75. https://doi.org/10.21037/jlpm.2018.08.07

- Shahbaz, H.; M. Gupta. Creatinine clearance. StatPearls 2023, StatPearls Publishing.

Author Affiliation

1Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

ARTICLE INFO

Dr. Raushanara Akter, Professor, School of Pharmacy, Brac University, Bangladesh

Dr. Md. Ashraful Alam, Professor, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, North South University, Bangladesh